Selection from C.S. Peirce, “On the Algebra of Logic : A Contribution to the Philosophy of Notation” (1885)

§1. Three Kinds Of Signs (cont.)

For instance, take the syllogistic formula,

This is really a diagram of the relations of

and

The fact that the middle term occurs in the two premisses is actually exhibited, and this must be done or the notation will be of no value.

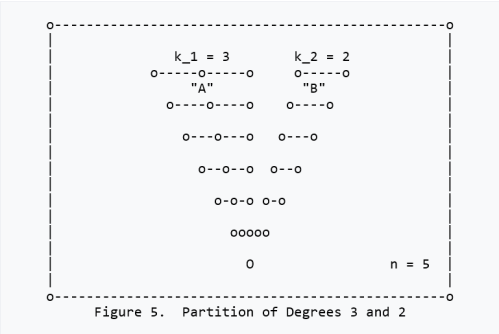

As for algebra, the very idea of the art is that it presents formulæ which can be manipulated, and that by observing the effects of such manipulation we find properties not to be otherwise discerned. In such manipulation, we are guided by previous discoveries which are embodied in general formulæ. These are patterns which we have the right to imitate in our procedure, and are the icons par excellence of algebra. The letters of applied algebra are usually tokens, but the etc. of a general formula, such as

are blanks to be filled up with tokens, they are indices of tokens. Such a formula might, it is true, be replaced by an abstractly stated rule (say that multiplication is distributive); but no application could be made of such an abstract statement without translating it into a sensible image. (3.363).

References

- Peirce, C.S. (1885), “On the Algebra of Logic : A Contribution to the Philosophy of Notation”, American Journal of Mathematics 7, 180–202.

- Peirce, C.S., Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vols. 1–6, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (eds.), vols. 7–8, Arthur W. Burks (ed.), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1931–1935, 1958. Volume 3 : Exact Logic (Published Papers), 1933. CP 3.359–403.

- Peirce, C.S., Writings of Charles S. Peirce : A Chronological Edition, Peirce Edition Project (eds.), Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN, 1981–. Volume 5 (1884–1886), 1993. Item 30, 162–190.

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science