§1. Three Kinds Of Signs

Any character or proposition either concerns one subject, two subjects, or a plurality of subjects. For example, one particle has mass, two particles attract one another, a particle revolves about the line joining two others. A fact concerning two subjects is a dual character or relation; but a relation which is a mere combination of two independent facts concerning the two subjects may be called degenerate, just as two lines are called a degenerate conic. In like manner a plural character or conjoint relation is to be called degenerate if it is a mere compound of dual characters. (3.359).

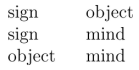

A sign is in a conjoint relation to the thing denoted and to the mind. If this triple relation is not of a degenerate species, the sign is related to its object only in consequence of a mental association, and depends upon a habit. Such signs are always abstract and general, because habits are general rules to which the organism has become subjected. They are, for the most part, conventional or arbitrary. They include all general words, the main body of speech, and any mode of conveying a judgment. For the sake of brevity I will call them tokens. [Note. Peirce more frequently calls these symbols.] (3.360).

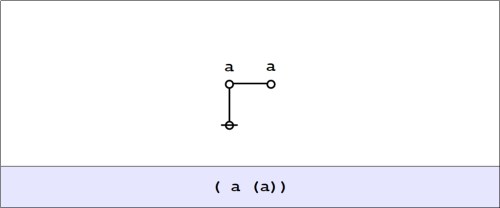

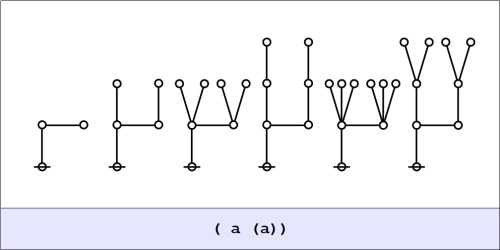

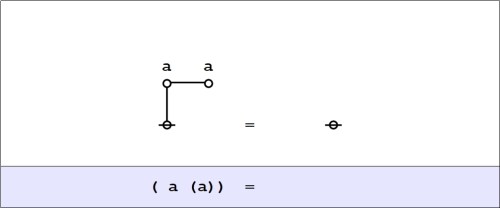

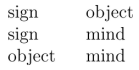

But if the triple relation between the sign, its object, and the mind, is degenerate, then of the three pairs

two at least are in dual relations which constitute the triple relation. One of the connected pairs must consist of the sign and its object, for if the sign were not related to its object except by the mind thinking of them separately, it would not fulfill the function of a sign at all. Supposing, then, the relation of the sign to its object does not lie in a mental association, there must be a direct dual relation of the sign to its object independent of the mind using the sign. In the second of the three cases just spoken of, this dual relation is not degenerate, and the sign signifies its object solely by virtue of being really connected with it. Of this nature are all natural signs and physical symptoms. I call such a sign an index, a pointing finger being the type of this class.

The index asserts nothing; it only says “There!” It takes hold of our eyes, as it were, and forcibly directs them to a particular object, and there it stops. Demonstrative and relative pronouns are nearly pure indices, because they denote things without describing them; so are the letters on a geometrical diagram, and the subscript numbers which in algebra distinguish one value from another without saying what those values are. (3.361).

The third case is where the dual relation between the sign and its object is degenerate and consists in a mere resemblance between them. I call a sign which stands for something merely because it resembles it, an icon. Icons are so completely substituted for their objects as hardly to be distinguished from them. Such are the diagrams of geometry. A diagram, indeed, so far as it has a general signification, is not a pure icon; but in the middle part of our reasonings we forget that abstractness in great measure, and the diagram is for us the very thing. So in contemplating a painting, there is a moment when we lose consciousness that it is not the thing, the distinction of the real and the copy disappears, and it is for the moment a pure dream — not any particular existence, and yet not general. At that moment we are contemplating an icon. (3.362).