Theme One is a program for constructing and transforming a particular species of graph‑theoretic data structures, forms designed to support a variety of fundamental learning and reasoning tasks.

The program evolved over the course of an exploration into the integration of contrasting types of activities involved in learning and reasoning, especially the types of algorithms and data structures capable of supporting all sorts of inquiry processes, from everyday problem solving to scientific investigation. In its current state, Theme One integrates over a common data structure fundamental algorithms for one type of inductive learning and one type of deductive reasoning.

We begin by describing the class of graph-theoretic data structures used by the program, as determined by their local and global features. It will be the usual practice to shift around and view these graphs at many different levels of detail, from their abstract definition to their concrete implementation, and many points in between.

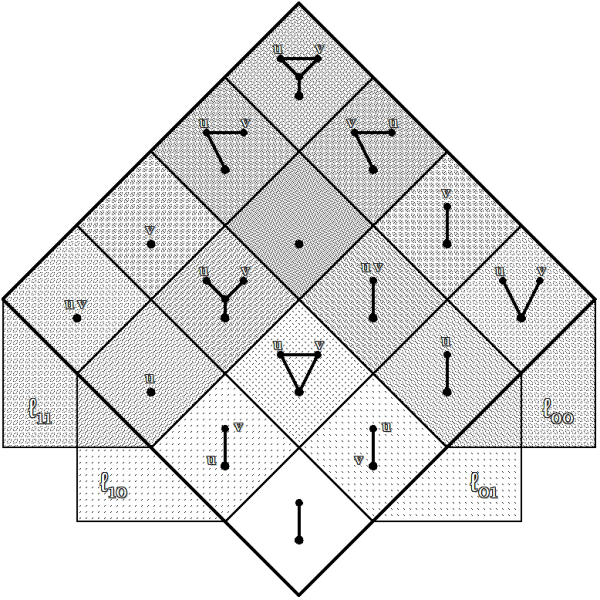

The main work of the Theme One program is achieved by building and transforming a single species of graph-theoretic data structures. In their abstract form these structures are closely related to the graphs called cacti and conifers in graph theory, so we’ll generally refer to them under those names.

The Idea↑Form Flag

The graph-theoretic data structures used by the program are built up from a basic data structure called an idea-form flag. That structure is defined as a pair of Pascal data types by means of the following specifications.

- An idea is a pointer to a form.

- A form is a record consisting of:

- A sign of type char;

- Four pointers, as, up, on, by, of type idea;

- A code of type numb, that is, an integer in [0, max integer].

Represented in terms of digraphs, or directed graphs, the combination of an idea pointer and a form record is most easily pictured as an arc, or directed edge, leading to a node labeled with the other data, in this case, a letter and a number.

At the roughest but quickest level of detail, an idea of a form can be drawn as follows.

When it is necessary to fill in more detail, the following schematic pattern can be used.

The idea-form type definition determines the local structure of the whole host of graphs used by the program, including a motley array of ephemeral buffers, temporary scratch lists, and other graph-theoretic data structures used for their transient utilities at specific points in the program.

I will put off discussing the more incidental graph structures until the points where they actually arise, focusing here on the particular varieties of cactoid graphs which constitute the main formal media of the program’s operation.

Resources

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Ontolog Forum

cc: FB | Theme One Program • Structural Modeling • Systems Science