A semiotic equivalence relation (SER) is a special type of equivalence relation arising in the analysis of sign relations. Generally speaking, any equivalence relation induces a partition of the underlying set of elements, known as the domain or space of the relation, into a family of equivalence classes. In the case of a SER the equivalence classes are called semiotic equivalence classes (SECs) and the partition is called a semiotic partition (SEP).

The sign relations and

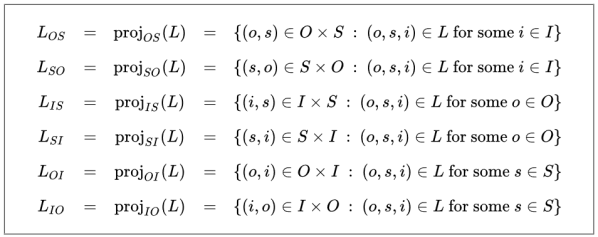

have many interesting properties over and above those possessed by sign relations in general. Some of these properties have to do with the relation between signs and their interpretant signs, as reflected in the projections of

and

on the

-plane, notated as

and

respectively. The dyadic relations on

induced by these projections are also referred to as the connotative components of the corresponding sign relations, notated as

and

respectively. Tables 6a and 6b show the corresponding connotative components.

A nice property of the sign relations and

is that their connotative components

and

form a pair of equivalence relations on their common syntactic domain

This type of equivalence relation is called a semiotic equivalence relation (SER) because it equates signs having the same meaning to some interpreter.

Each of the semiotic equivalence relations, partitions the collection of signs into semiotic equivalence classes. This makes for a strong form of representation in that the structure of the interpreters’ common object domain

is reflected or reconstructed, part for part, in the structure of each one’s semiotic partition of the syntactic domain

But it needs to be observed that the semiotic partitions for interpreters

and

are not identical, indeed, they are orthogonal to each other. This allows us to regard the form of these partitions as corresponding to an objective structure or invariant reality, but not the literal sets of signs themselves, independent of the individual interpreter’s point of view.

Information about the contrasting patterns of semiotic equivalence corresponding to the interpreters and

is summarized in Tables 7a and 7b. The form of these Tables serves to explain what is meant by saying the SEPs for

and

are orthogonal to each other.

References

- Peirce, C.S. (1902), “Parts of Carnegie Application” (L 75), in Carolyn Eisele (ed., 1976), The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce, vol. 4, 13–73. Online.

- Awbrey, J.L., and Awbrey, S.M. (1995), “Interpretation as Action : The Risk of Inquiry”, Inquiry : Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines 15(1), pp. 40–52. Archive. Journal. Online.

Resources

Document History

Portions of the above article were adapted from the following sources under the GNU Free Documentation License, under other applicable licenses, or by permission of the copyright holders.

- Sign Relation • OEIS Wiki

- Sign Relation • InterSciWiki

- Sign Relation • MyWikiBiz

- Sign Relation • PlanetMath

- Sign Relation • Wikiversity

- Sign Relation • Wikipedia

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog • Peirce List (1) (2) • Structural Modeling • Systems Science