Re: Differential Logic, Dynamic Systems, Tangent Functors • 1

Seeing as how quasi-neural models and the recurring issues of symbolic vs. connectionist paradigms have come round again, I thought I might revisit work I began initially in that context, investigating logical, qualitative, and symbolic analogues of systems studied by McClelland, Rumelhart, and the Parallel Distributed Processing Group, and especially Stephen Grossberg’s competition-cooperation models.

⁂

People interested in category theory as applied to systems may wish to check out the following article, reporting work I carried out while engaged in a systems engineering program at Oakland University.

The problem addressed is a longstanding one, namely, building bridges to negotiate the gap between qualitative and quantitative descriptions of complex phenomena, like those we meet in analyzing and engineering systems, especially intelligent systems endowed with a capacity for processing information and acquiring knowledge of objective reality.

One way the problem arises has to do with describing change in logical, qualitative, and symbolic terms, long before we grasp the reality beneath the appearances firmly enough to cast it in measured, quantitative, real-number form.

Development on the quantitative shore got no further than a Sisyphean beachhead until the invention of differential calculus by Leibniz and Newton, after which things advanced by leaps and bounds. And there’s our clue what we need to do on the qualitative shore, namely, develop the missing logical analogue of differential calculus.

With that preamble …

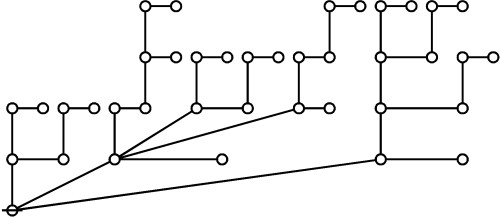

Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems

This article develops a differential extension of propositional calculus and applies it to a context of problems arising in dynamic systems. The work pursued here is coordinated with a parallel application that focuses on neural network systems, but the dependencies are arranged to make the present article the main and the more self-contained work, to serve as a conceptual frame and a technical background for the network project.

The reading continues at Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems

Resources

cc: Category Theory • Cybernetics (1) (2) (3) • Ontolog Forum (1) (2)

cc: Structural Modeling (1) (2) • Systems Science (1) (2)

cc: FB | Differential Logic • Laws of Form • Peirce List