We pick up the text at §3. Application of the Algebraic Signs to Logic.

Peirce’s 1870 “Logic of Relatives” • Selection 1

Use of the Letters

The letters of the alphabet will denote logical signs.

Now logical terms are of three grand classes.

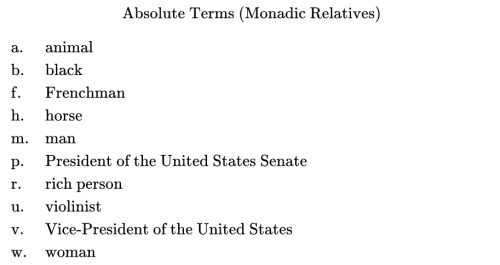

The first embraces those whose logical form involves only the conception of quality, and which therefore represent a thing simply as “a ──”. These discriminate objects in the most rudimentary way, which does not involve any consciousness of discrimination. They regard an object as it is in itself as such (quale); for example, as horse, tree, or man. These are absolute terms.

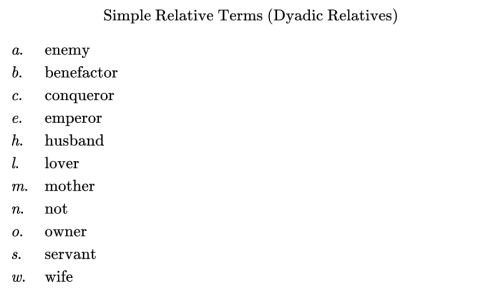

The second class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of relation, and which require the addition of another term to complete the denotation. These discriminate objects with a distinct consciousness of discrimination. They regard an object as over against another, that is as relative; as father of, lover of, or servant of. These are simple relative terms.

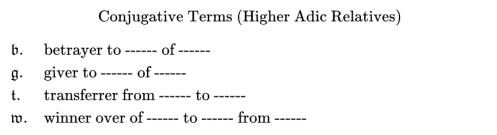

The third class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of bringing things into relation, and which require the addition of more than one term to complete the denotation. They discriminate not only with consciousness of discrimination, but with consciousness of its origin. They regard an object as medium or third between two others, that is as conjugative; as giver of ── to ──, or buyer of ── for ── from ──. These may be termed conjugative terms.

The conjugative term involves the conception of third, the relative that of second or other, the absolute term simply considers an object. No fourth class of terms exists involving the conception of fourth, because when that of third is introduced, since it involves the conception of bringing objects into relation, all higher numbers are given at once, inasmuch as the conception of bringing objects into relation is independent of the number of members of the relationship. Whether this reason for the fact that there is no fourth class of terms fundamentally different from the third is satisfactory of not, the fact itself is made perfectly evident by the study of the logic of relatives.

(Peirce, CP 3.63)

One thing that strikes me about the above passage is a pattern of argument I can recognize as invoking a closure principle. This is a figure of reasoning Peirce uses in three other places: his discussion of continuous predicates, his definition of a sign relation, and his formulation of the pragmatic maxim itself.

One might also call attention to the following two statements:

No fourth class of terms exists involving the conception of fourth, because when that of third is introduced, since it involves the conception of bringing objects into relation, all higher numbers are given at once, inasmuch as the conception of bringing objects into relation is independent of the number of members of the relationship.

Resources

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)