Inquiry and Analogy • Application of Higher Order Propositions to Quantification Theory

Our excursion into the expanding landscape of higher order propositions has come round to the point where we can begin to open up new perspectives on quantificational logic.

Though it may be all the same from a purely formal point of view, it does serve intuition to adopt a slightly different interpretation for the two‑valued space we take as the target of our basic indicator functions. In that spirit we declare a novel type of existence-valued functions where

is a pair of values indicating whether anything exists in the cells of the underlying universe of discourse. As usual, we won’t be too picky about the coding of those functions, reverting to binary codes whenever the intended interpretation is clear enough.

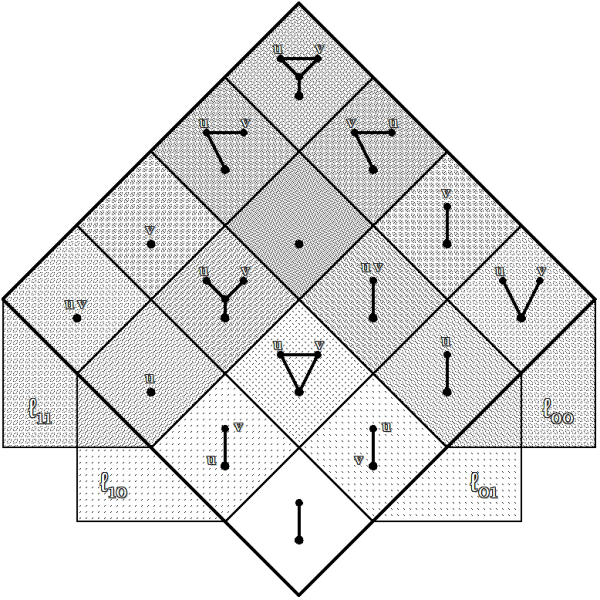

With that interpretation in mind we observe the following correspondence between classical quantifications and higher order indicator functions.

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Boolean Function

- Boolean-Valued Function

- Logical Conjunction

- Minimal Negation Operator

- Introduction to Inquiry Driven Systems

- Functional Logic • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3

- Cactus Language • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • References • Document History

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Ontolog • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science