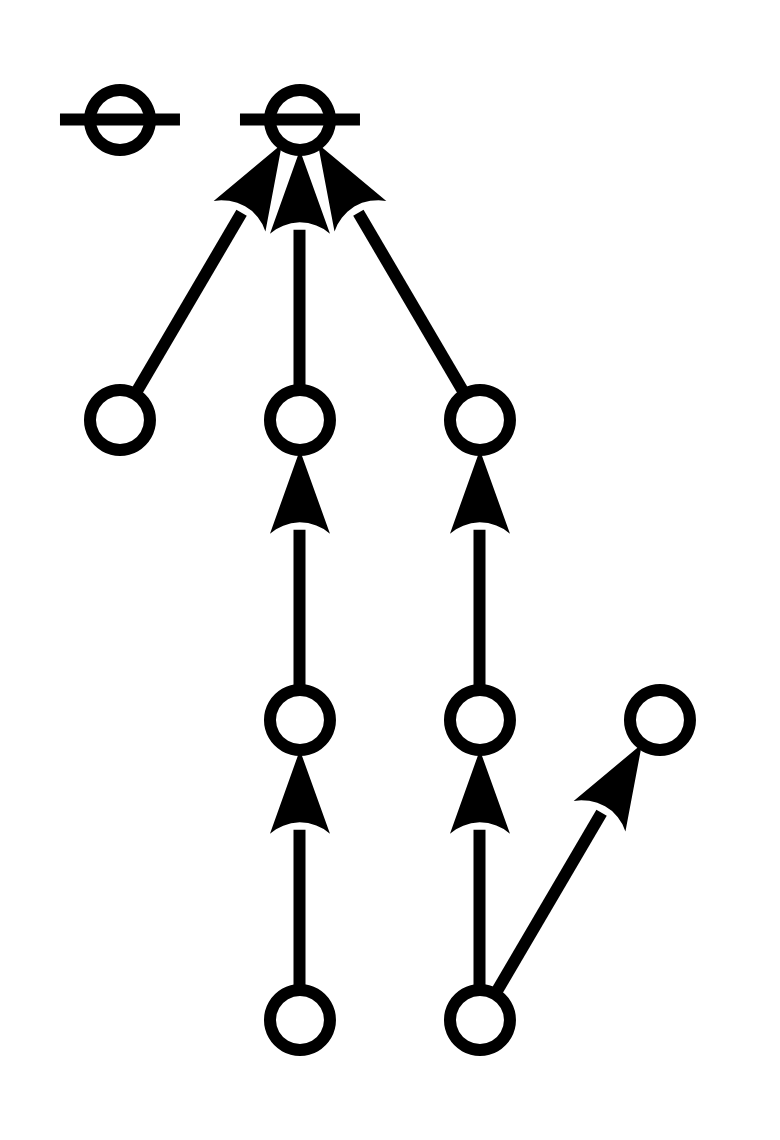

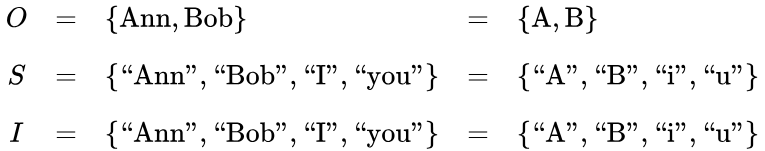

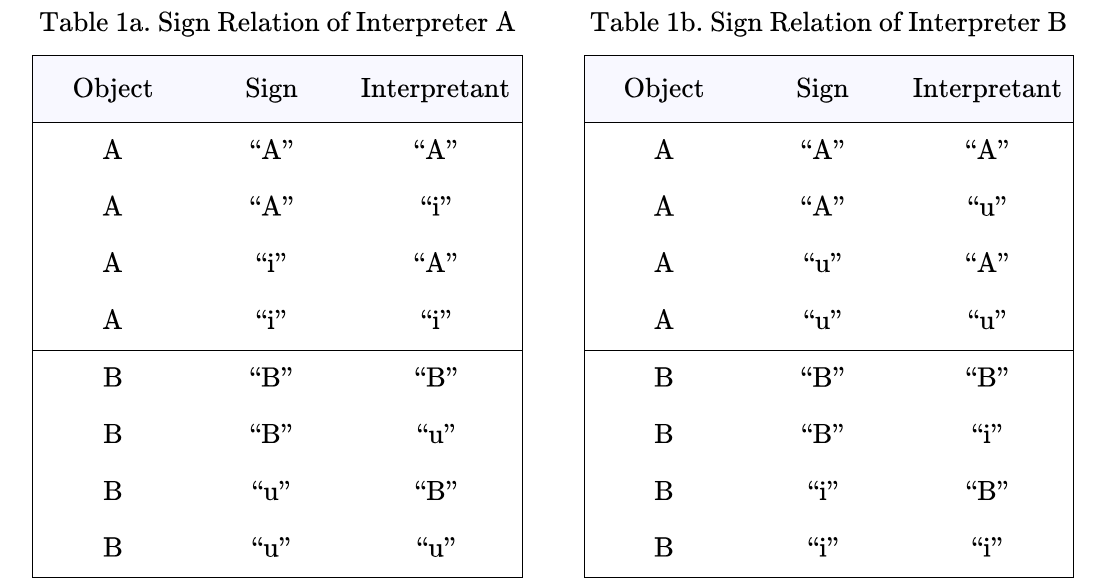

The dyadic components of sign relations have graph‑theoretic representations, as digraphs (or directed graphs), which provide concise pictures of their structural and potential dynamic properties.

By way of terminology, a directed edge is called an arc from point

to point

and a self‑loop

is called a sling at

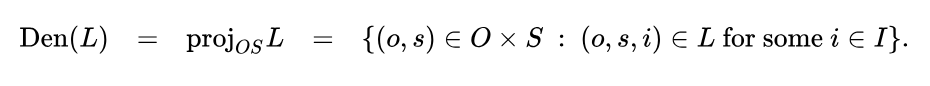

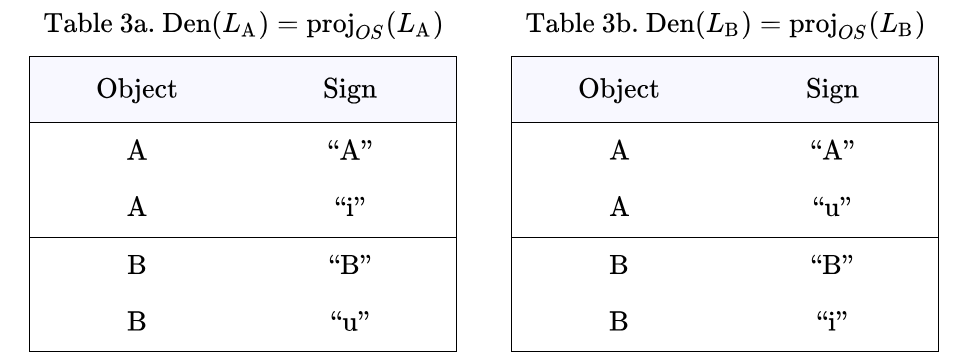

The denotative components and

can be represented as digraphs on the six points of their common world set

The arcs are given as follows.

- Denotative Component

has an arc from each point of

to

has an arc from each point of

to

- Denotative Component

has an arc from each point of

to

has an arc from each point of

to

and

can be interpreted as transition digraphs which chart the succession of steps or the connection of states in a computational process. If the graphs are read in that way, the denotational arcs summarize the upshots of the computations involved when the interpreters

and

evaluate the signs in

according to their own frames of reference.

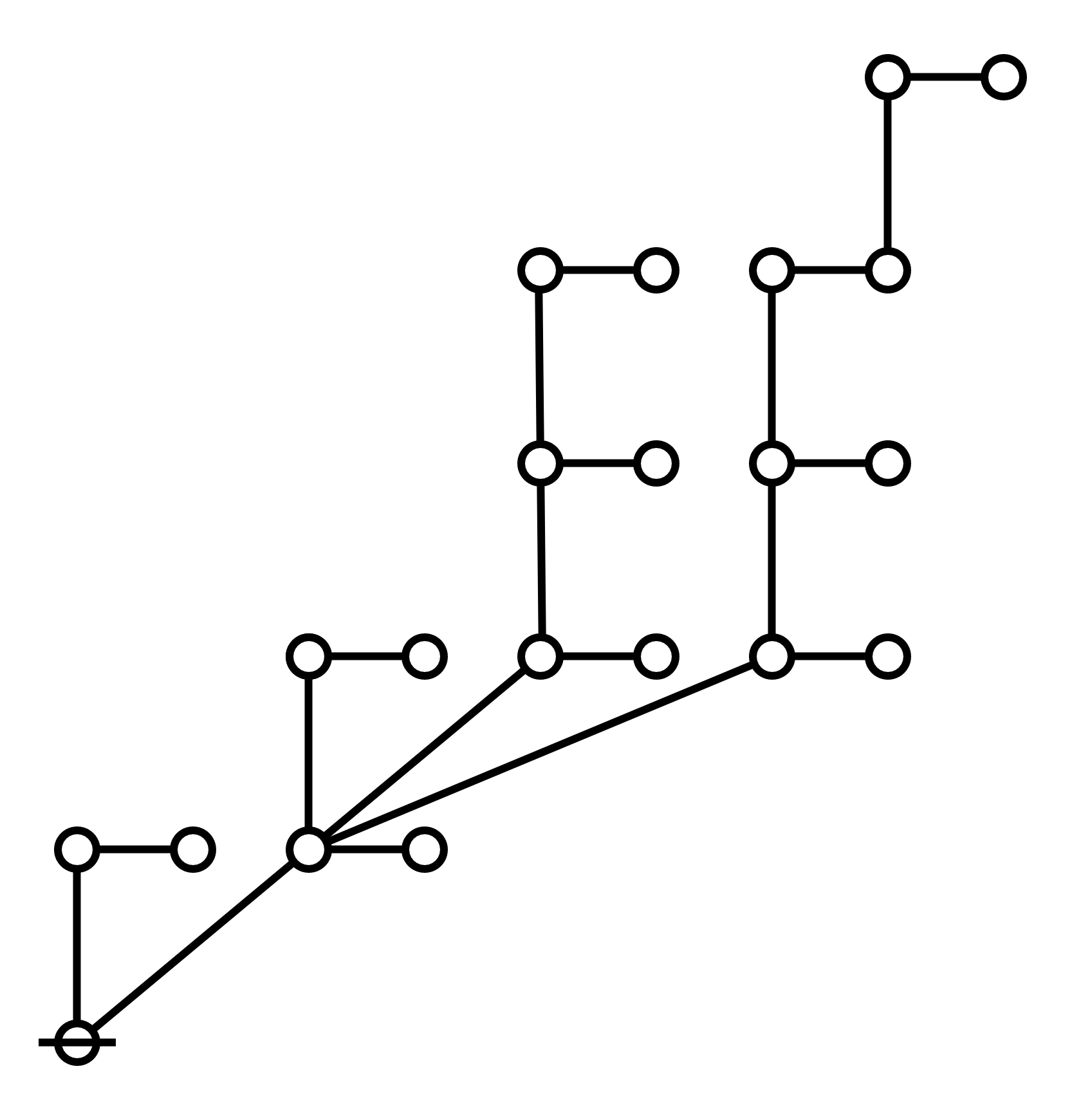

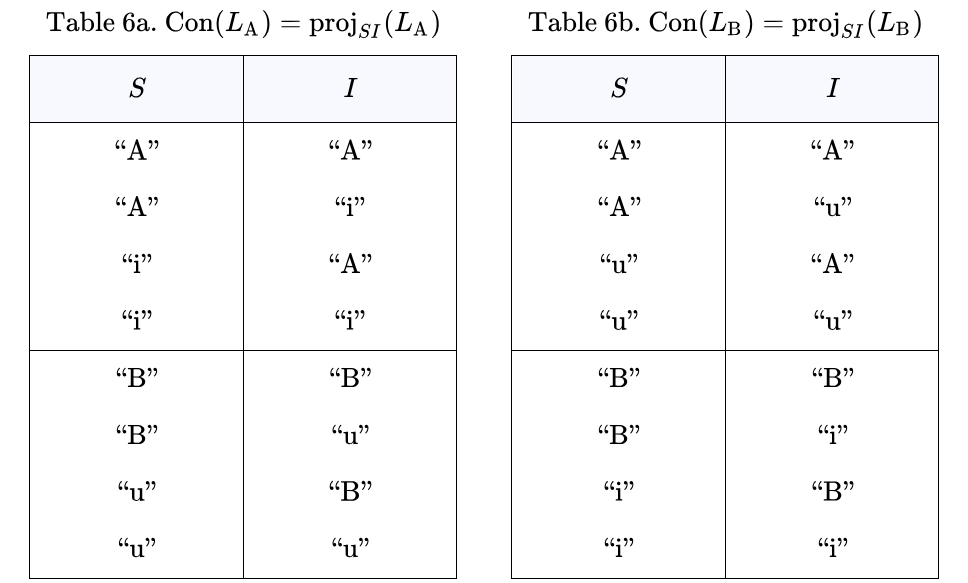

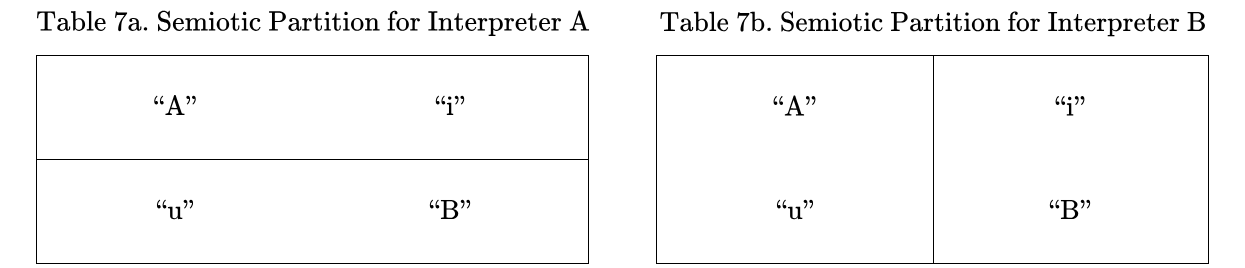

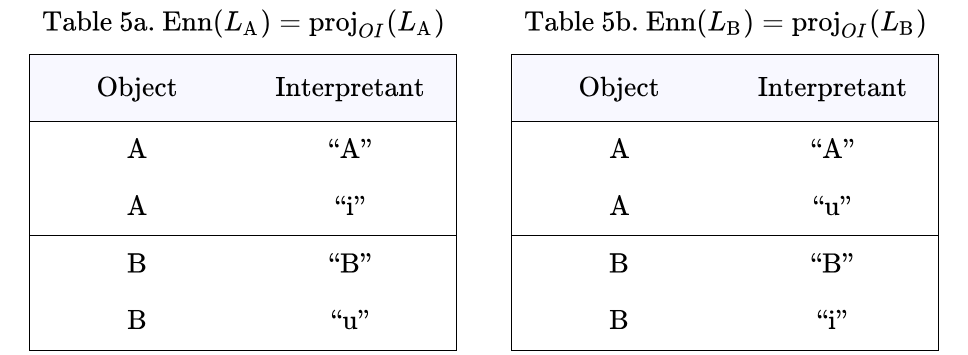

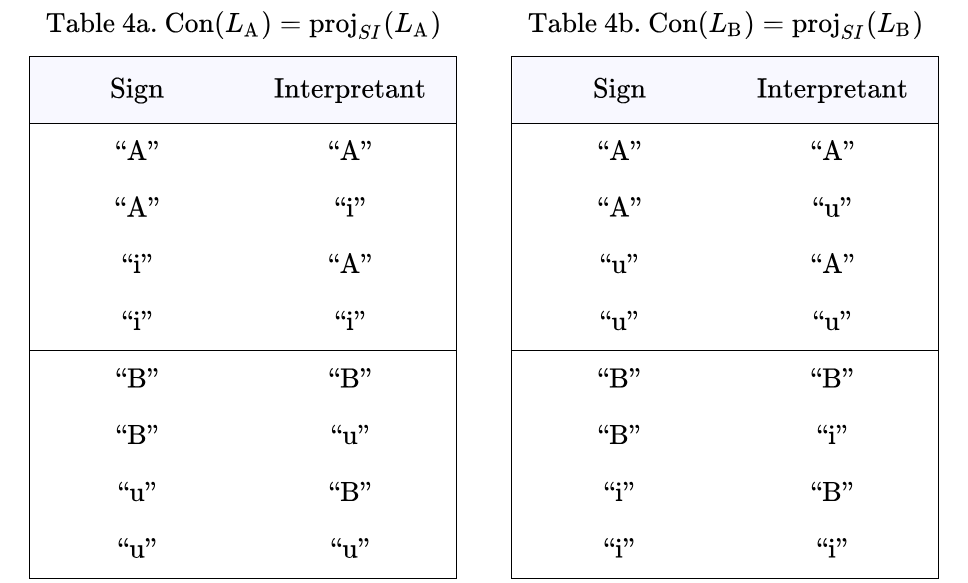

The connotative components and

can be represented as digraphs on the four points of their common syntactic domain

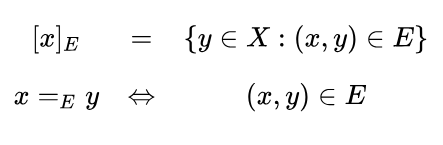

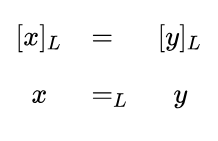

Since

and

are semiotic equivalence relations, their digraphs conform to the pattern manifested by all digraphs of equivalence relations. In general, a digraph of an equivalence relation falls into connected components which correspond to the parts of the associated partition, with a complete digraph on the points of each part, and no other arcs. In the present case, the arcs are given as follows.

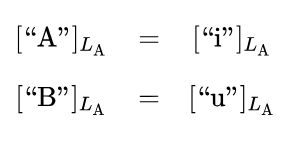

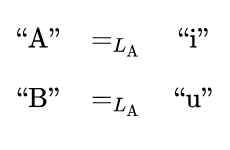

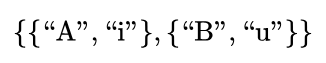

- Connotative Component

has the structure of a semiotic equivalence relation on

There is a sling at each point ofarcs in both directions between the points of

and arcs in both directions between the points of

- Connotative Component

has the structure of a semiotic equivalence relation on

There is a sling at each point ofarcs in both directions between the points of

and arcs in both directions between the points of

Taken as transition digraphs, and

highlight the associations permitted between equivalent signs, as the equivalence is judged by the respective interpreters

and

Resources

- Sign Relation • OEIS • MyWikiBiz • Wikiversity

- Survey of Semiotics, Semiosis, Sign Relations

cc: Academia.edu • Laws of Form • Research Gate • Syscoi

cc: Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science