Re: Functional Logic • Inquiry and Analogy • 8

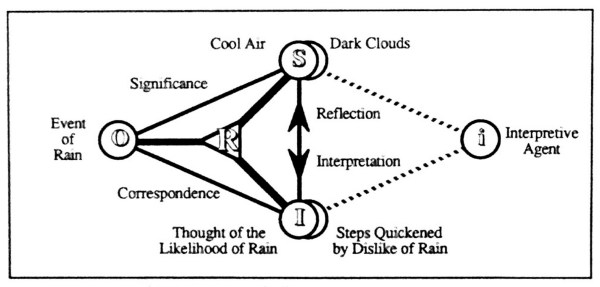

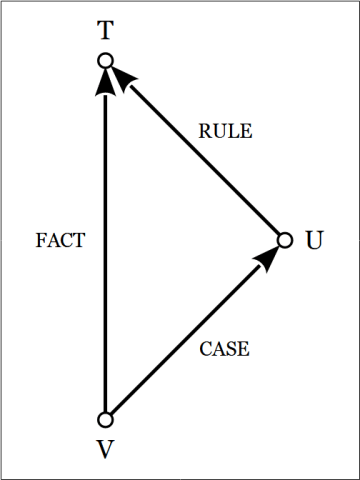

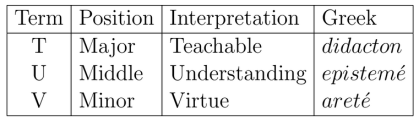

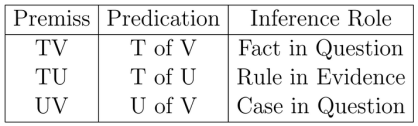

Post 8 used the following Figure to illustrate Dewey’s example of a simple inquiry process.

John Mingers shared the following observations.

- JM:

- Liked the example — a couple of questions/comments.

- In the diagram you have included with the Triadic sign, although with dotted lines, an interpretive agent. Now I thought that Peirce was a bit cagey about this. Wasn’t he clear that the interpretant was not to be identified with an actual interpreter? What is your thinking on this?

- I do agree that there needs to be an interpreter but does it need to be a person? Surely it could be any organism that can interact with relations?

The cool air is something our hero interprets as a sign of rain and his thought of rain is an interpretant sign of the very same object. The relation between the interpretant sign and the interpretive agent is clear enough as far as a beginning level of description goes. But a fully pragmatic, semiotic, and system-theoretic account will demand a more fine-grained analysis of what goes on in the inquiry process.

Speaking very roughly, an interpreter is any agent or system — animal, vegetable, or mineral — which actualizes or embodies a triadic sign relation.

Several passages from Peirce will help to flesh out the bare abstractions. I’ll begin collecting them on the linked blog page and discuss them further as we proceed.

Previous Discussions

- 2020

- 2018

- 2001

- 2000

- Semiotics Formalization • Standard Upper Ontology

Related Resources

- Information = Comprehension × Extension • Selection 18

- Inquiry Driven Systems • C’est Moi

- Interpreters and Interpretants

Reference

- Awbrey, J.L., and Awbrey, S.M. (1995), “Interpretation as Action : The Risk of Inquiry”, Inquiry : Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines 15(1), 40–52. Archive. Journal. Online (doc) (pdf).

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Ontolog • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science