Peirce identifies inference with a process he describes as symbolization. Let us consider what that might imply.

I am going, next, to show that inference is symbolization and that the puzzle of the validity of scientific inference lies merely in this superfluous comprehension and is therefore entirely removed by a consideration of the laws of information. (467).

Even if it were only a weaker analogy between inference and symbolization, a principle of logical continuity — what in physics is called a correspondence principle — would suggest parallels between steps of reasoning in the neighborhood of exact inferences and signs in the vicinity of genuine symbols. This would lead us to expect a correspondence between degrees of inference and degrees of symbolization that extends from exact to approximate or non-demonstrative inferences and from genuine to approximate or degenerate symbols.

For this purpose, I must call your attention to the differences there are in the manner in which different representations stand for their objects.

In the first place there are likenesses or copies — such as statues, pictures, emblems, hieroglyphics, and the like. Such representations stand for their objects only so far as they have an actual resemblance to them — that is agree with them in some characters. The peculiarity of such representations is that they do not determine their objects — they stand for anything more or less; for they stand for whatever they resemble and they resemble everything more or less.

The second kind of representations are such as are set up by a convention of men or a decree of God. Such are tallies, proper names, &c. The peculiarity of these conventional signs is that they represent no character of their objects.

Likenesses denote nothing in particular; conventional signs connote nothing in particular.

The third and last kind of representations are symbols or general representations. They connote attributes and so connote them as to determine what they denote. To this class belong all words and all conceptions. Most combinations of words are also symbols. A proposition, an argument, even a whole book may be, and should be, a single symbol. (467–468).

In addition to Aristotle, the influence of Kant on Peirce is very strongly marked in these earliest expositions. The invocations of “conceptions of the understanding”, the “use of concepts” and thus of symbols in reducing the manifold of extension, and the not so subtle hint of the synthetic à priori in Peirce’s discussion, not only of natural kinds but also of the kinds of signs leading up to genuine symbols, can all be recognized as pervasive Kantian themes.

In order to draw out these themes and see how Peirce was led to develop their leading ideas, let us bring together our previous Figures, abstracting from their concrete details, and see if we can figure out what is going on here.

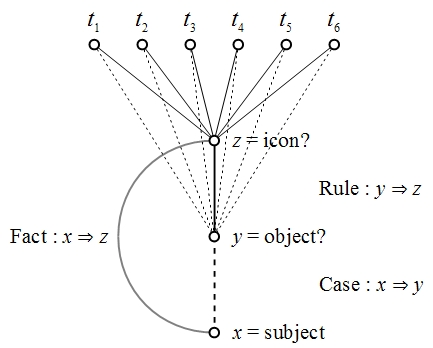

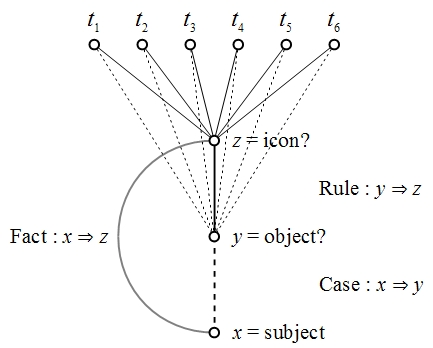

Figure 3 shows an abductive step of inquiry, as taken on the cue of an iconic sign.

Figure 3. Conjunctive Predicate z, Abduction of Case x ⇒ y

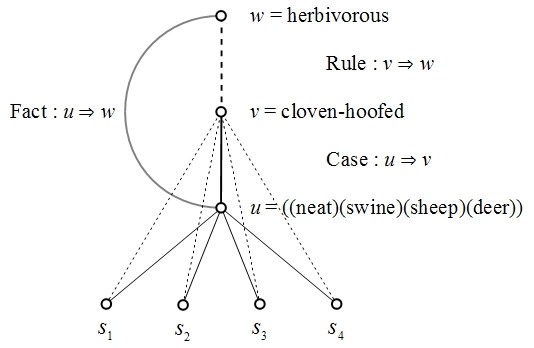

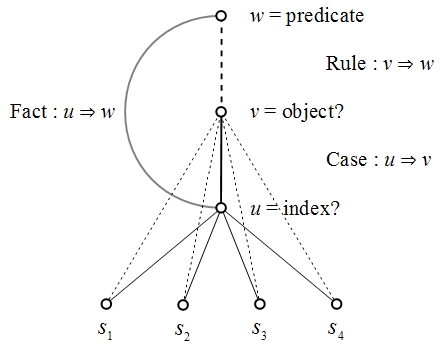

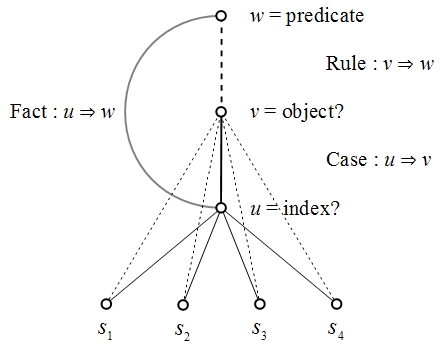

Figure 4 shows an inductive step of inquiry, as taken on the cue of an indicial sign.

Figure 4. Disjunctive Subject u, Induction of Rule v ⇒ w

To be continued …

Reference

- Peirce, C.S. (1866), “The Logic of Science, or, Induction and Hypothesis”, Lowell Lectures of 1866, pp. 357–504 in Writings of Charles S. Peirce : A Chronological Edition, Volume 1, 1857–1866, Peirce Edition Project, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 1982.

Resources