If we stand back for a moment to regard the structure of an implicational logic, such as Whitehead and Russell’s, we see that it is fully contained in that of an equivalence logic. The difference is in the kind of step used. In one case expressions are detached at the point of implication, in the other they are detached at the point of equivalence.

G. Spencer Brown • Laws of Form

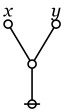

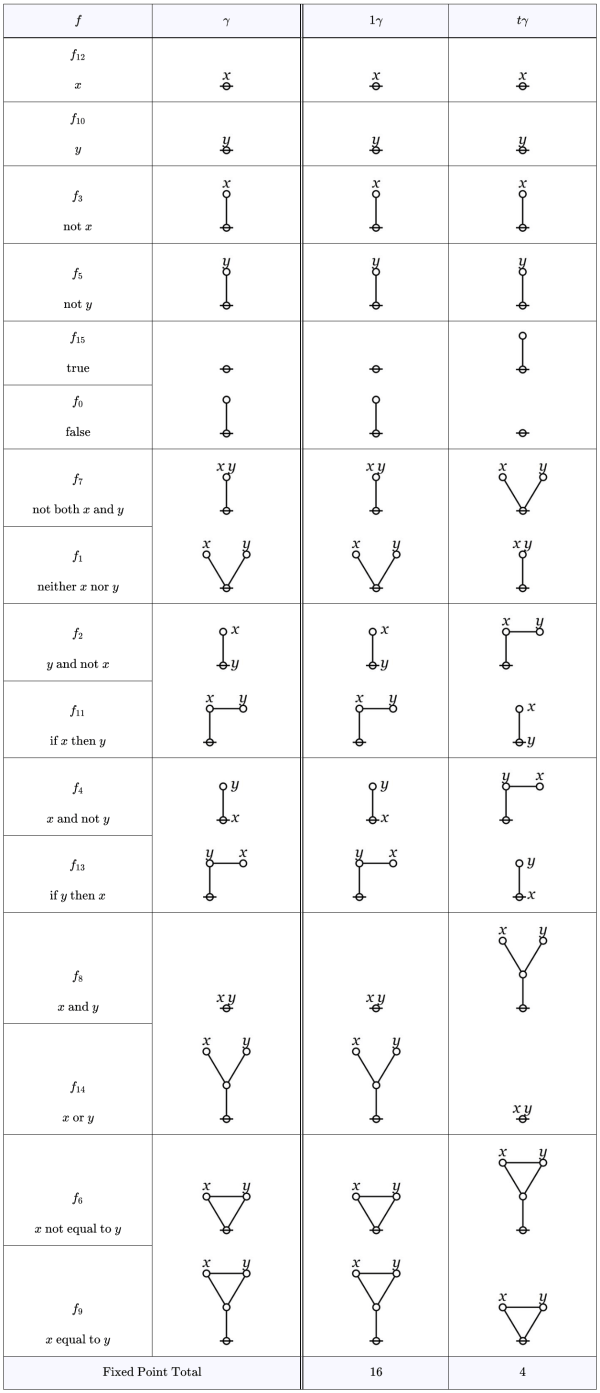

We have been exploring the properties of a simple but elegant formal system exhibiting useful applications to logic. This very simplicity helps us focus on core features of formal systems and logical reasoning in a far less cluttered environment than the general run of logical systems. Earlier we touched on the theme of duality sourcing the radiation of mathematical form into logical subject matter, a theme we’ll touch on again.

But while we have the simple but critical example of Double Negation in our sights let’s use it to illustrate another central feature of logical graphs bearing on the mathematical infrastructure of logic. This is the power of using equational inference over and above implicational inference in proofs.

Here again is the formal equation corresponding to the principle of double negation, shown below in graph-theoretic and traversal-string forms.

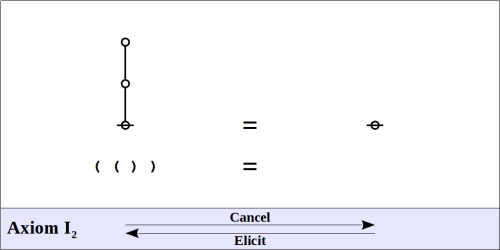

Whether any principle is taken for an axiom or has to be proven as a theorem depends on the formal system at hand. In the present system double negation is a consequence of the following set of axioms.

Axioms

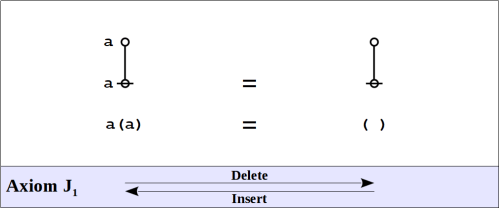

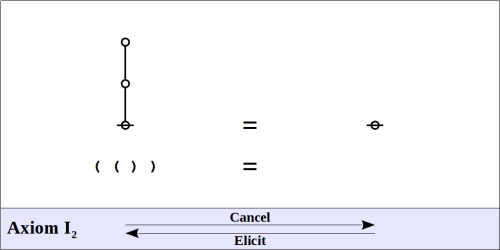

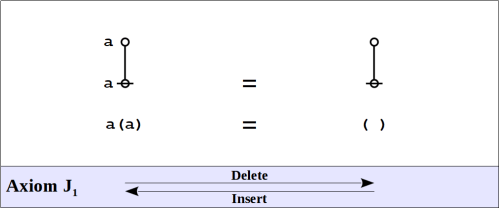

The formal system of logical graphs is defined by a foursome of formal equations, called initials when regarded purely formally, in abstraction from potential interpretations, and called axioms when interpreted as logical equivalences. There are two arithmetic initials and two algebraic initials, as shown below.

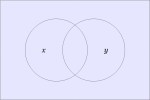

Arithmetic Initials

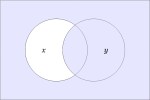

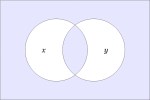

Algebraic Initials

Logical Interpretation

One way of assigning logical meaning to the initial equations is known as the entitative interpretation (En). Under En, the axioms read as follows.

![\begin{array}{ccccc} \mathrm{I_1} & : & \text{true} ~ \text{or} ~ \text{true} & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{I_2} & : & \text{not} ~ \text{true} & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_1} & : & a ~ \text{or} ~ \text{not} ~ a & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_2} & : & (a ~ \text{or} ~ b) ~ \text{and} ~ (a ~ \text{or} ~ c) & = & a ~ \text{or} ~ (b ~ \text{and} ~ c) \end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bccccc%7D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+a++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+b%29+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+c%29++%26+%3D+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%28b+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+c%29++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

Another way of assigning logical meaning to the initial equations is known as the existential interpretation (Ex). Under Ex, the axioms read as follows.

![\begin{array}{ccccc} \mathrm{I_1} & : & \text{false} ~ \text{and} ~ \text{false} & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{I_2} & : & \text{not} ~ \text{false} & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_1} & : & a ~ \text{and} ~ \text{not} ~ a & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_2} & : & (a ~ \text{and} ~ b) ~ \text{or} ~ (a\ \text{and}\ c) & = & a ~ \text{and} ~ (b ~ \text{or} ~ c) \end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bccccc%7D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+a+++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+b%29+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%28a%5C+%5Ctext%7Band%7D%5C+c%29++%26+%3D+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%28b+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+c%29++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

Equational Inference

Formal proofs in what follows employ a variation on Spencer Brown’s annotation scheme to mark each step of proof according to which axiom is called to license the corresponding step of syntactic transformation, whether it applies to graphs or to strings. All the axioms in the above set have the form of equations. This means the inference steps they license are all reversible. The proof annotation scheme employs a double bar  to mark this fact, though it will often be left to the reader to decide which of the two possible directions is the one required for applying the indicated axiom.

to mark this fact, though it will often be left to the reader to decide which of the two possible directions is the one required for applying the indicated axiom.

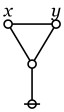

Here is the proof of Double Negation.

The actual business of proof is a far more strategic affair than the simple cranking of inference rules might suggest. Part of the reason for this lies in the circumstance that implicational inference rules combine the moving forward of a state of inquiry with the losing of whatever information along the way one did not think immediately relevant, at least, not as viewed in the local focus and short hauls of moment to moment progress of the proof in question. Over the long haul, this has the pernicious side-effect of one being strategically forced to reconstruct much of the information one had strategically thought to forget in earlier stages of the proof, where before the proof started may be counted as an earlier stage of the proof in view.

This is one of the reasons it is instructive to study equational inference rules. Equational forms of reasoning are paramount in mathematics but they are less familiar to the student of conventional logic textbooks, who may find a few surprises here.

Resources

Reference

- Spencer Brown, G. (1969), Laws of Form, George Allen and Unwin, London, UK, p. 118.

cc: Cybernetics • Laws of Form • FB | Logical Graphs • Ontolog Forum • Peirce List

• Structural Modeling • Systems Science