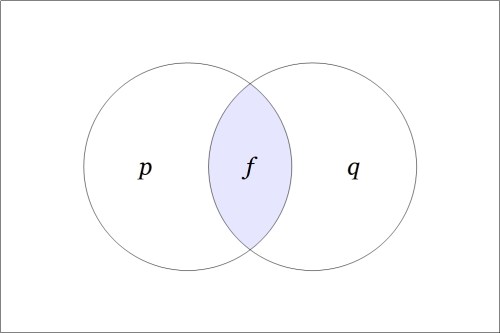

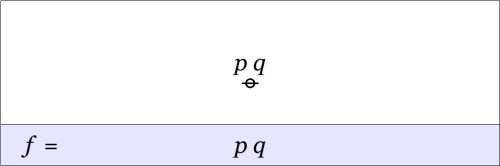

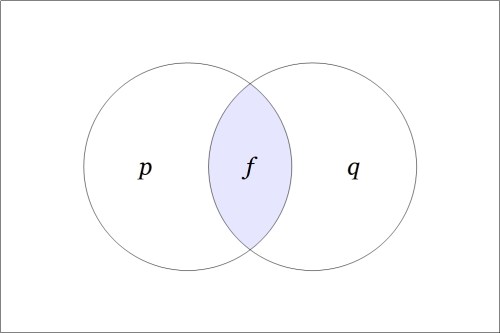

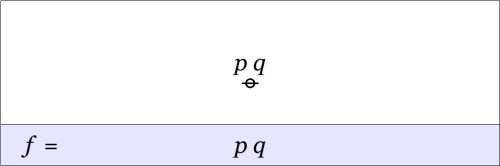

Let’s run through the initial example again, keeping an eye on the meanings of the formulas which develop along the way. We begin with a proposition or a boolean function  whose venn diagram and cactus graph are shown below.

whose venn diagram and cactus graph are shown below.

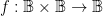

A function like  has an abstract type and a concrete type. The abstract type is what we invoke when we write things like

has an abstract type and a concrete type. The abstract type is what we invoke when we write things like  or

or  The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or “units” of the case, which can be explained as follows.

The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or “units” of the case, which can be explained as follows.

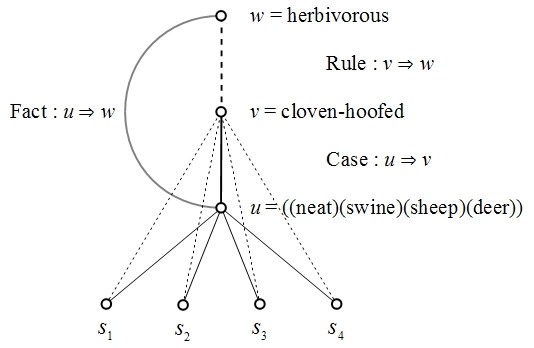

Let  be the set of values

be the set of values

Let  be the set of values

be the set of values

Then interpret the usual propositions about  as functions of the concrete type

as functions of the concrete type

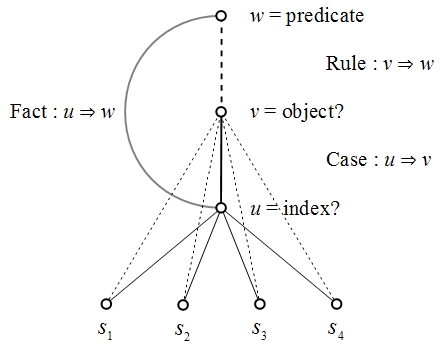

We are going to consider various operators on these functions. An operator  is a function which takes one function

is a function which takes one function  into another function

into another function

The first couple of operators we need are logical analogues of two which play a founding role in the classical finite difference calculus, namely, the following.

The difference operator  written here as

written here as

The enlargement operator, written here as

These days,  is more often called the shift operator.

is more often called the shift operator.

In order to describe the universe in which these operators operate, it is necessary to enlarge the original universe of discourse. Starting from the initial space  its (first order) differential extension

its (first order) differential extension  is constructed according to the following specifications.

is constructed according to the following specifications.

where:

![\begin{array}{rcc} X & = & P \times Q \\[4pt] \mathrm{d}X & = & \mathrm{d}P \times \mathrm{d}Q \\[4pt] \mathrm{d}P & = & \{ \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}p \texttt{)}, ~ \mathrm{d}p \} \\[4pt] \mathrm{d}Q & = & \{ \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}q \texttt{)}, ~ \mathrm{d}q \} \end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Brcc%7D++X+%26+%3D+%26+P+%5Ctimes+Q++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7DX+%26+%3D+%26+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7DP+%5Ctimes+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7DQ++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7DP+%26+%3D+%26+%5C%7B+%5Ctexttt%7B%28%7D+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7Dp+%5Ctexttt%7B%29%7D%2C+%7E+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7Dp+%5C%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7DQ+%26+%3D+%26+%5C%7B+%5Ctexttt%7B%28%7D+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7Dq+%5Ctexttt%7B%29%7D%2C+%7E+%5Cmathrm%7Bd%7Dq+%5C%7D++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

The interpretations of these new symbols can be diverse, but the easiest option for now is just to say  means “change

means “change  ” and

” and  means “change

means “change  ”.

”.

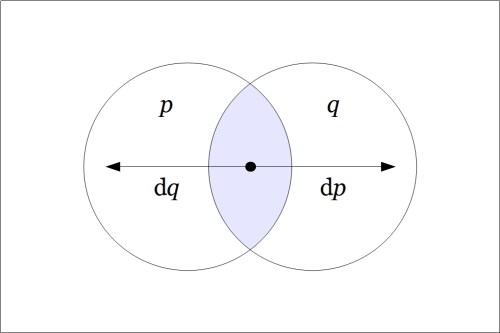

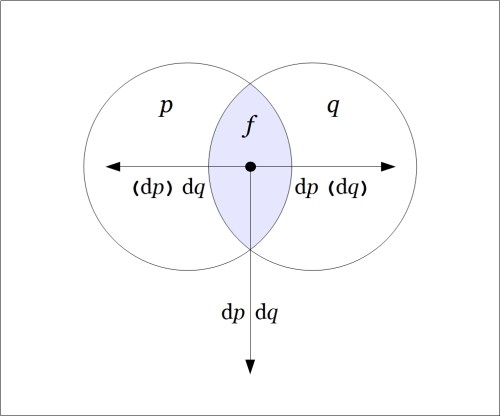

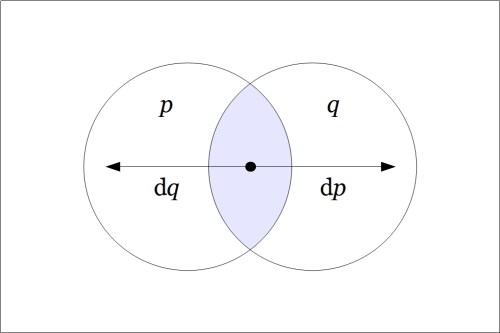

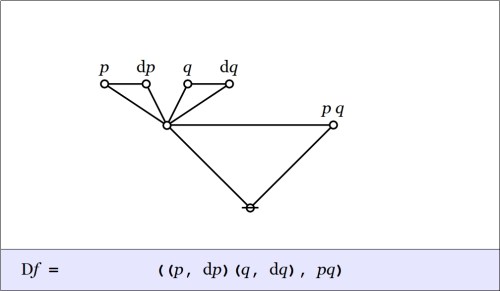

Drawing a venn diagram for the differential extension  requires four logical dimensions,

requires four logical dimensions,  but it is possible to project a suggestion of what the differential features

but it is possible to project a suggestion of what the differential features  and

and  are about on the 2‑dimensional base space

are about on the 2‑dimensional base space  by drawing arrows crossing the boundaries of the basic circles in the venn diagram for

by drawing arrows crossing the boundaries of the basic circles in the venn diagram for  reading an arrow as

reading an arrow as  if it crosses the boundary between

if it crosses the boundary between  and

and  in either direction and reading an arrow as

in either direction and reading an arrow as  if it crosses the boundary between

if it crosses the boundary between  and

and  in either direction, as indicated in the following figure.

in either direction, as indicated in the following figure.

Propositions are formed on differential variables, or any combination of ordinary logical variables and differential logical variables, in the same ways propositions are formed on ordinary logical variables alone. For example, the proposition  says the same thing as

says the same thing as  in other words, there is no change in

in other words, there is no change in  without a change in

without a change in

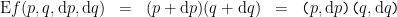

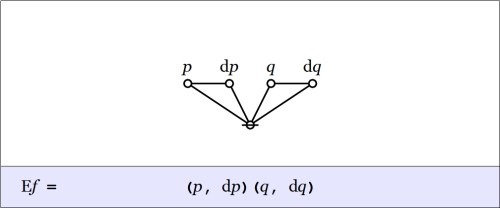

Given the proposition  over the space

over the space  the (first order) enlargement of

the (first order) enlargement of  is the proposition

is the proposition  over the differential extension

over the differential extension  defined by the following formula.

defined by the following formula.

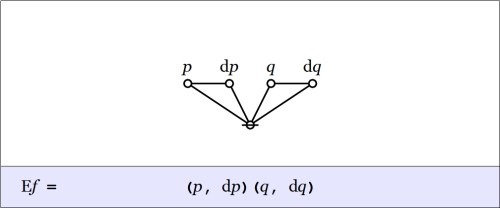

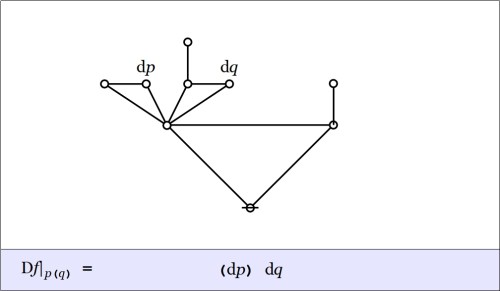

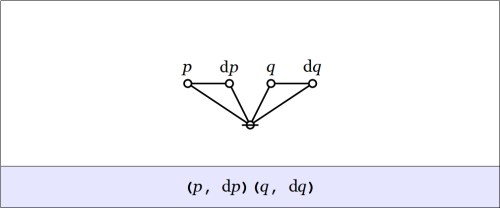

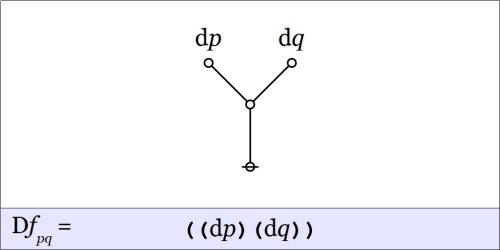

In the example  the enlargement

the enlargement  is computed as follows.

is computed as follows.

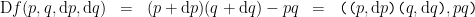

Given the proposition  over

over  the (first order) difference of

the (first order) difference of  is the proposition

is the proposition  over

over  defined by the formula

defined by the formula  or, written out in full:

or, written out in full:

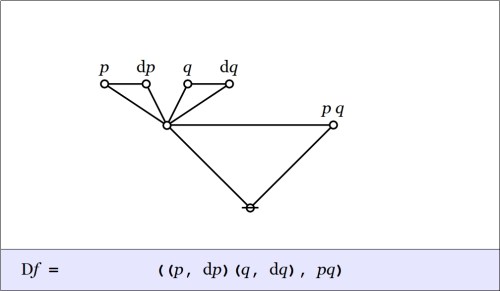

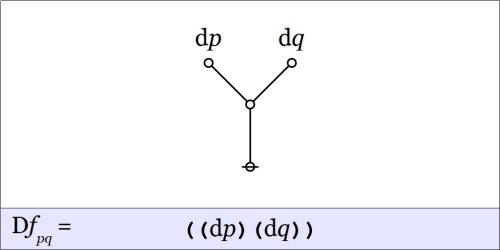

In the example  the difference

the difference  is computed as follows.

is computed as follows.

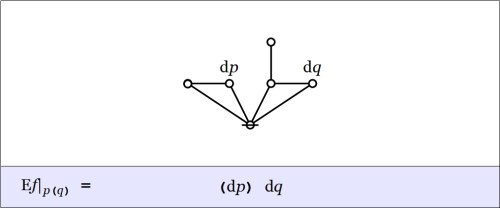

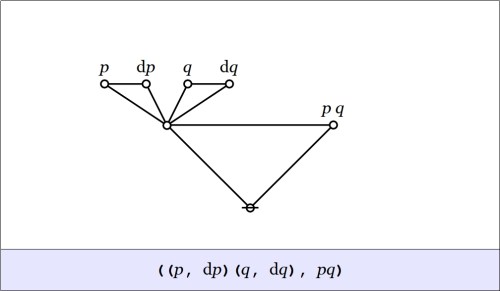

This brings us by the road meticulous to the point we reached at the end of the previous post. There we evaluated the above proposition, the first order difference of conjunction  at a single location in the universe of discourse, namely, at the point picked out by the singular proposition

at a single location in the universe of discourse, namely, at the point picked out by the singular proposition  in terms of coordinates, at the place where

in terms of coordinates, at the place where  and

and  That evaluation is written in the form

That evaluation is written in the form  or

or  and we arrived at the locally applicable law which may be stated and illustrated as follows.

and we arrived at the locally applicable law which may be stated and illustrated as follows.

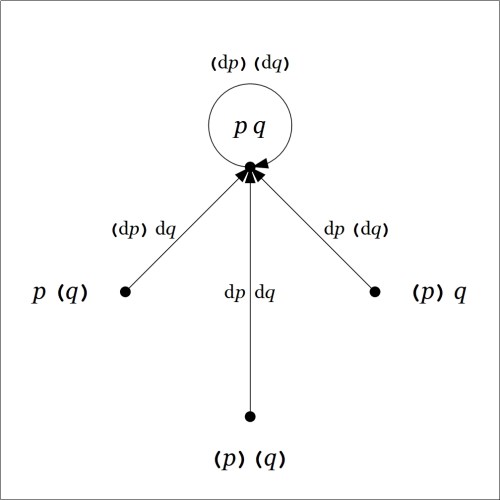

The venn diagram shows the analysis of the inclusive disjunction  into the following exclusive disjunction.

into the following exclusive disjunction.

The differential proposition  may be read as saying “change

may be read as saying “change  or change

or change  or both”. And this can be recognized as just what you need to do if you happen to find yourself in the center cell and require a complete and detailed description of ways to escape it.

or both”. And this can be recognized as just what you need to do if you happen to find yourself in the center cell and require a complete and detailed description of ways to escape it.

Resources

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Research Gate

and abstract type

Our inquiry into the differential aspects of logical conjunction will pay dividends as we study the actions of

and

on this family of forms.