Excerpt from C.S. Peirce, “Minute Logic” (1902), CP 2.144–148

2.2. Why Study Logic?

2.2.5. Reasoning and Expectation

144. But since you propose to study logic, you have more or less faith in reasoning, as affording knowledge of the truth. Now reasoning is a very different thing indeed from the percept, or even from perceptual facts. For reasoning is essentially a voluntary act, over which we exercise control. If it were not so, logic would be of no use at all. For logic is, in the main, criticism of reasoning as good or bad. Now it is idle so to criticize an operation which is beyond all control, correction, or improvement.

145. You have, therefore, to inquire, first, in what sense you have any faith in reasoning, seeing that its conclusions cannot in the least resemble the percepts, upon which alone implicit reliance is warranted. Conclusions of reasoning can little resemble even the perceptual facts. For besides being involuntary, these latter are strictly memories of what has taken place in the recent past, while all conclusions of reasoning partake of the general nature of expectations of the future. What two things can be more disparate than a memory and an expectation?

⁂

147. The second branch of the question, when you have decided in what your faith in reasoning consists, will inquire just what it is that justifies that faith. The simulation of doubt about things indubitable or not really doubted is no more wholesome than is any other humbug; yet the precise specification of the evidence for an undoubted truth often in logic throws a brilliant light in one direction or in another, now pointing to a corrected formulation of the proposition, now to a better comprehension of its relations to other truths, again to some valuable distinctions, etc.

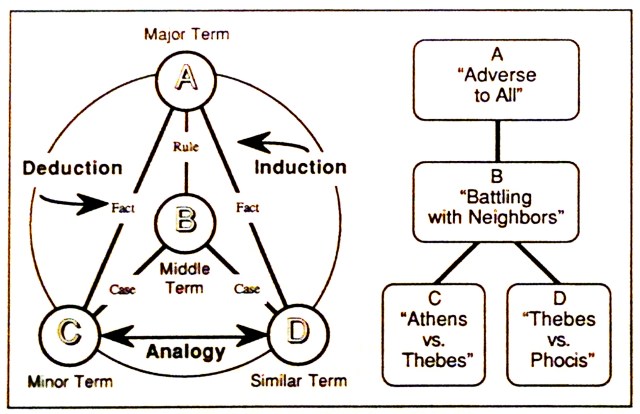

148. As to the former branch of this question, it will be found upon consideration that it is precisely the analogy of an inferential conclusion to an expectation which furnishes the key to the matter. An expectation is a habit of imagining. A habit is not an affection of consciousness; it is a general law of action, such that on a certain general kind of occasion a man will be more or less apt to act in a certain general way. An imagination is an affection of consciousness which can be directly compared with a percept in some special feature, and be pronounced to accord or disaccord with it. Suppose for example that I slip a cent into a slot, and expect on pulling a knob to see a little cake of chocolate appear. My expectation consists in, or at least involves, such a habit that when I think of pulling the knob, I imagine I see a chocolate coming into view. When the perceptual chocolate comes into view, my imagination of it is a feeling of such a nature that the percept can be compared with it as to size, shape, the nature of the wrapper, the color, taste, flavor, hardness and grain of what is within. Of course, every expectation is a matter of inference. What an inference is we shall soon see more exactly than we need just now to consider. For our present purpose it is sufficient to say that the inferential process involves the formation of a habit. For it produces a belief, or opinion; and a genuine belief, or opinion, is something on which a man is prepared to act, and is therefore, in a general sense, a habit. A belief need not be conscious.

Peirce, C.S., Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vols. 1–6, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (eds.), vols. 7–8, Arthur W. Burks (ed.), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1931–1935, 1958. Volume 2 : Elements of Logic, 1932. Reprinted with corrections, 1960.