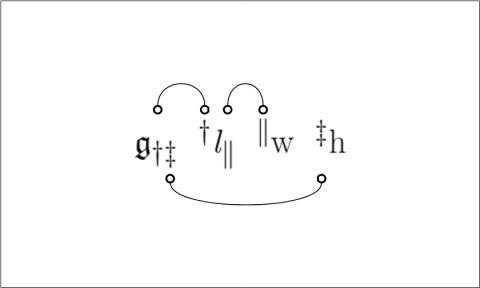

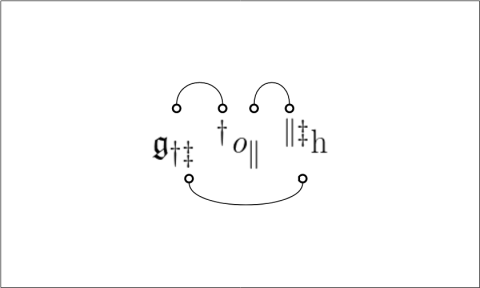

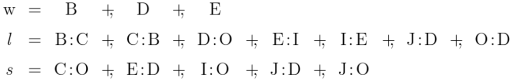

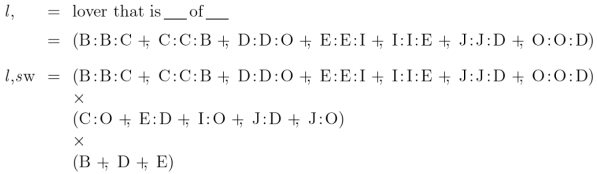

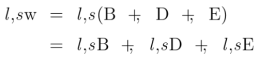

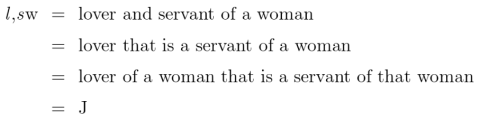

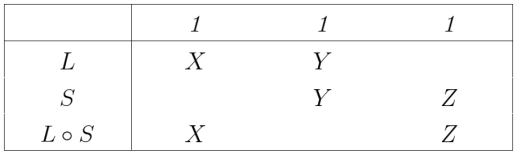

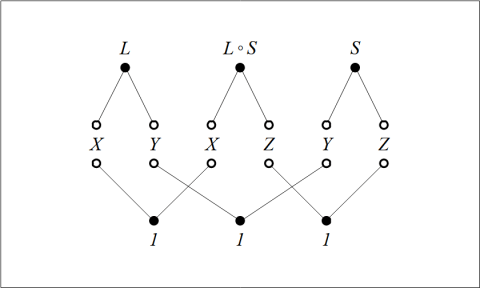

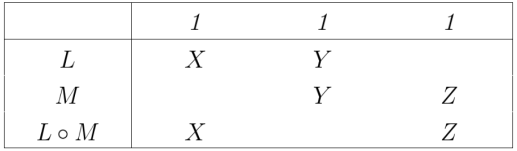

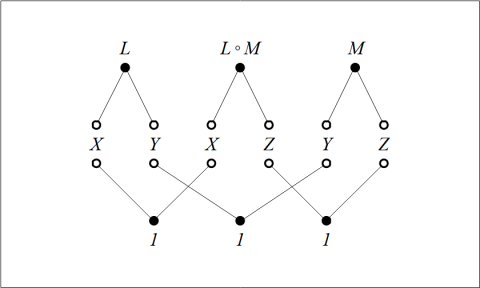

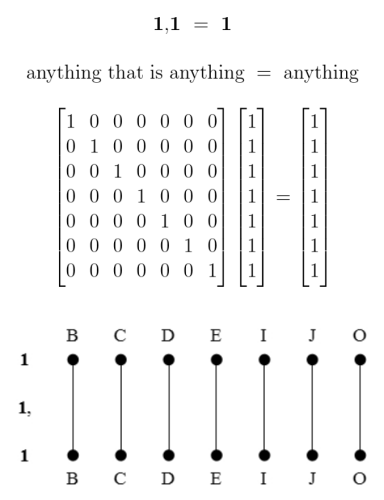

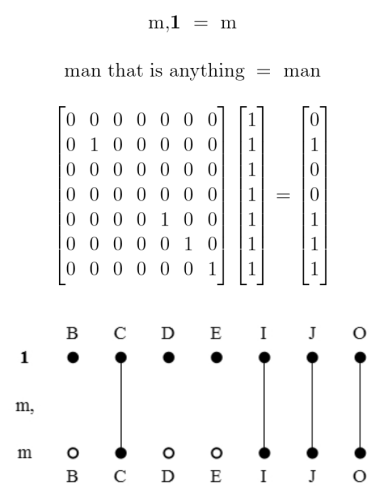

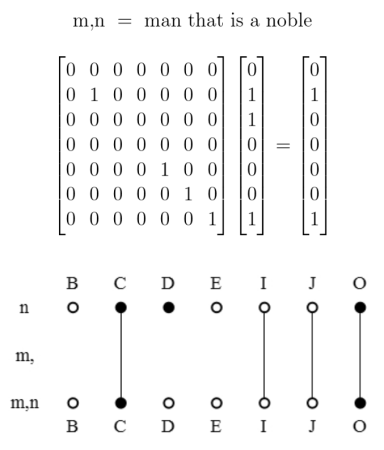

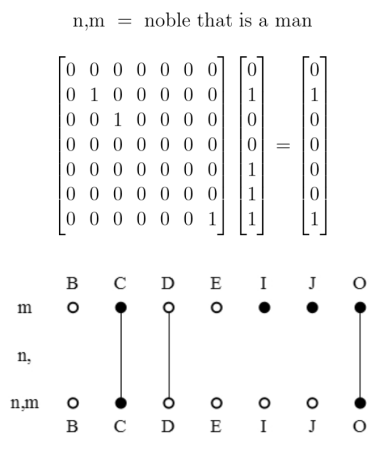

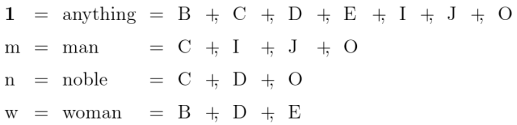

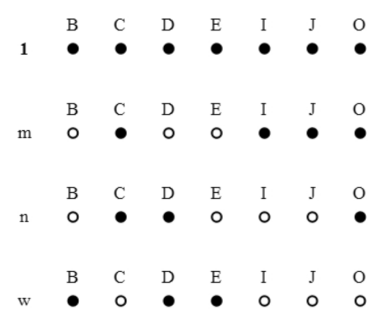

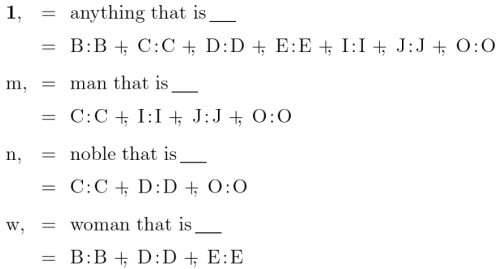

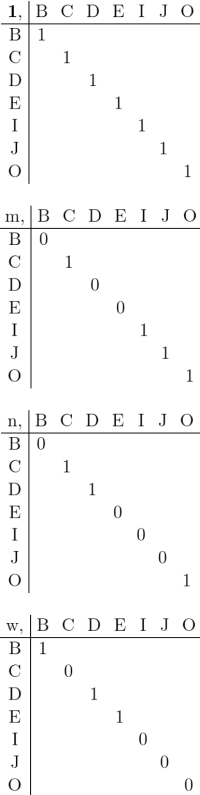

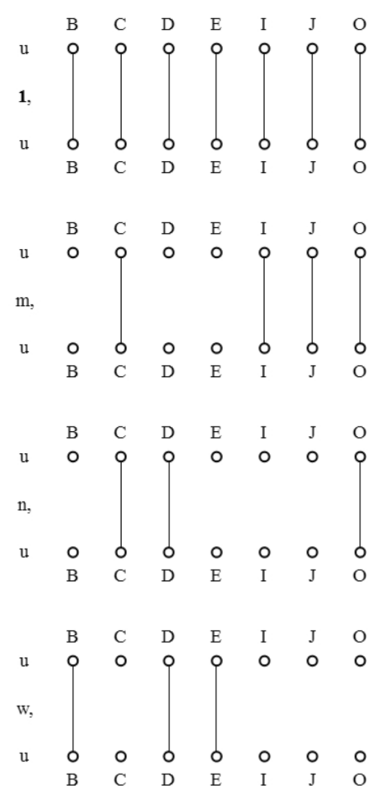

We have been using several styles of picture to illustrate relative terms and the relations they denote. Let’s now examine the relationships which exist among the variety of visual schemes. Two examples of relative multiplication we considered before are diagrammed again in Figures 11 and 12.

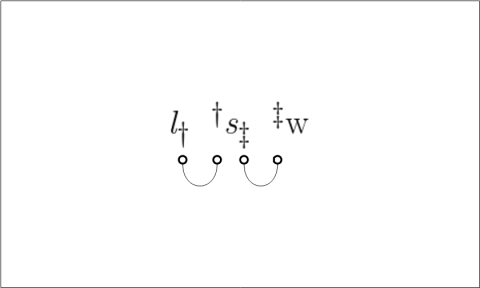

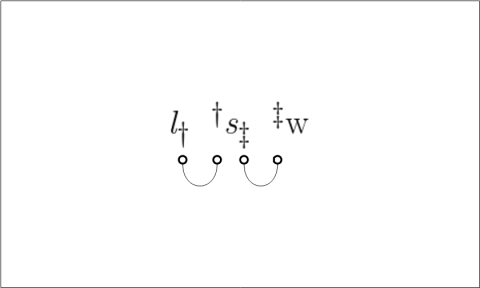

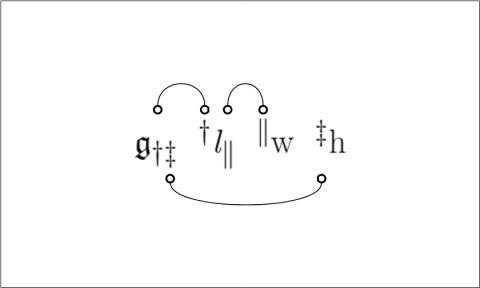

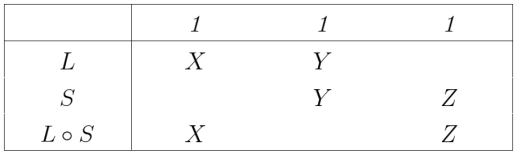

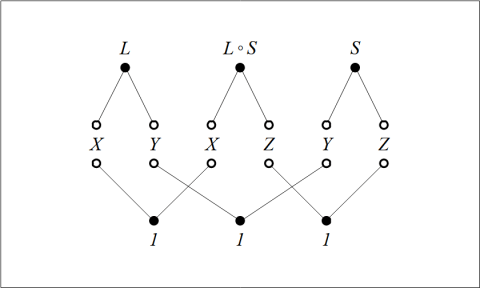

Figures 11 and 12 employ one of the styles of syntax Peirce used for relative multiplication, to which I added lines of identity to connect the corresponding marks of reference. Forms like these show the anatomy of the relative terms themselves, while the forms in Table 13 and Figure 14 are adapted to show the structures of the objective relations they denote.

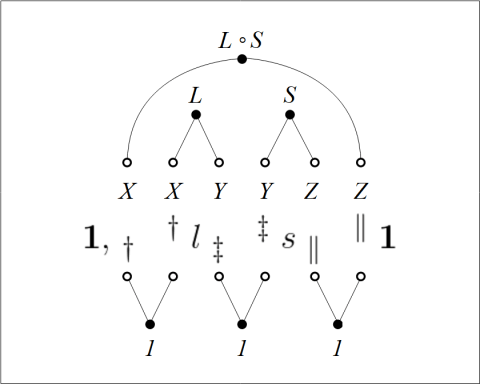

There are many ways Peirce might have gotten from his 1870 Notation for the Logic of Relatives to his more evolved systems of Logical Graphs. It is interesting to speculate on how the metamorphosis might have been accomplished by way of transformations acting on these nascent forms of syntax and taking place not too far from the pale of its means, that is, as nearly as possible according to the rules and permissions of the initial system itself.

In Existential Graphs, a relation is represented by a node whose degree is the adicity of that relation, and which is adjacent via lines of identity to the nodes representing its correlative relations, including as a special case any of its terminal individual arguments.

In the 1870 Logic of Relatives, implicit lines of identity are invoked by the subjacent numbers and marks of reference only when a correlate of some relation is the rèlate of some relation. Thus, the principal rèlate, which is not a correlate of any explicit relation, is not singled out in this way.

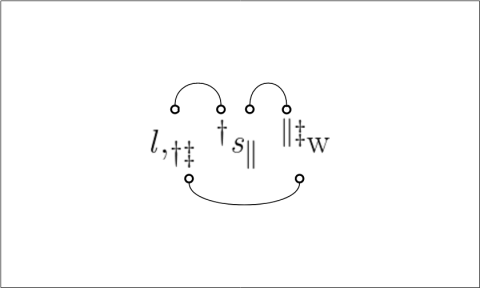

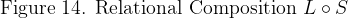

Remarkably enough, the comma modifier itself provides us with a mechanism to abstract the logic of relations from the logic of relatives, and thus to forge a possible link between the syntax of relative terms and the more graphical depiction of the objective relations themselves.

Figure 15 demonstrates this possibility, posing a transitional case between the style of syntax in Figure 11 and the picture of composition in Figure 14.

In this composite sketch the diagonal extension  of the universe

of the universe  is invoked up front to anchor an explicit line of identity for the leading rèlate of the composition, while the terminal argument

is invoked up front to anchor an explicit line of identity for the leading rèlate of the composition, while the terminal argument  is generalized to the whole universe

is generalized to the whole universe  Doing this amounts to an act of abstraction from the particular application to

Doing this amounts to an act of abstraction from the particular application to  This form of universal bracketing isolates the serial composition of the relations

This form of universal bracketing isolates the serial composition of the relations  and

and  to form the composite

to form the composite

Resources

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)