NOF Said …

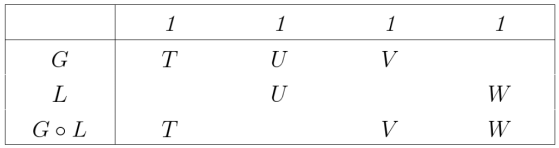

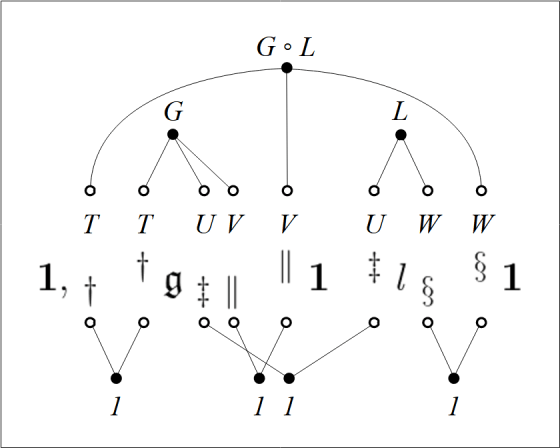

Let’s bring together the various things Peirce has said about the number of function up to this point in the paper.

NOF 1

I propose to assign to all logical terms, numbers; to an absolute term, the number of individuals it denotes; to a relative term, the average number of things so related to one individual. Thus in a universe of perfect men (men), the number of “tooth of” would be 32. The number of a relative with two correlates would be the average number of things so related to a pair of individuals; and so on for relatives of higher numbers of correlates. I propose to denote the number of a logical term by enclosing the term in square brackets, thus, ![[t].](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bt%5D.&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

(Peirce, CP 3.65)

NOF 2

But not only do the significations of  and

and  here adopted fulfill all absolute requirements, but they have the supererogatory virtue of being very nearly the same as the common significations. Equality is, in fact, nothing but the identity of two numbers; numbers that are equal are those which are predicable of the same collections, just as terms that are identical are those which are predicable of the same classes.

here adopted fulfill all absolute requirements, but they have the supererogatory virtue of being very nearly the same as the common significations. Equality is, in fact, nothing but the identity of two numbers; numbers that are equal are those which are predicable of the same collections, just as terms that are identical are those which are predicable of the same classes.

So, to write  is to say that 5 is part of 7, just as to write

is to say that 5 is part of 7, just as to write  is to say that Frenchmen are part of men. Indeed, if

is to say that Frenchmen are part of men. Indeed, if  then the number of Frenchmen is less than the number of men, and if

then the number of Frenchmen is less than the number of men, and if  then the number of Vice-Presidents is equal to the number of Presidents of the Senate; so that the numbers may always be substituted for the terms themselves, in case no signs of operation occur in the equations or inequalities.

then the number of Vice-Presidents is equal to the number of Presidents of the Senate; so that the numbers may always be substituted for the terms themselves, in case no signs of operation occur in the equations or inequalities.

(Peirce, CP 3.66)

NOF 3

It is plain that both the regular non-invertible addition and the invertible addition satisfy the absolute conditions. But the notation has other recommendations. The conception of taking together involved in these processes is strongly analogous to that of summation, the sum of 2 and 5, for example, being the number of a collection which consists of a collection of two and a collection of five. Any logical equation or inequality in which no operation but addition is involved may be converted into a numerical equation or inequality by substituting the numbers of the several terms for the terms themselves — provided all the terms summed are mutually exclusive.

Addition being taken in this sense, nothing is to be denoted by zero, for then

whatever is denoted by  ; and this is the definition of zero. This interpretation is given by Boole, and is very neat, on account of the resemblance between the ordinary conception of zero and that of nothing, and because we shall thus have

; and this is the definition of zero. This interpretation is given by Boole, and is very neat, on account of the resemblance between the ordinary conception of zero and that of nothing, and because we shall thus have

![[0] ~=~ 0.](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%5D+%7E%3D%7E+0.&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

(Peirce, CP 3.67)

NOF 4

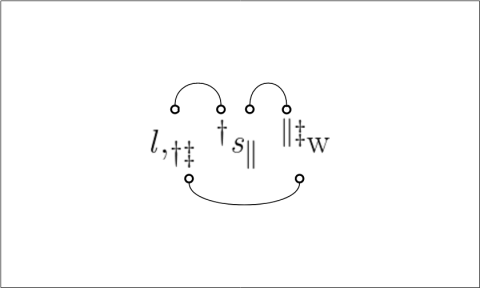

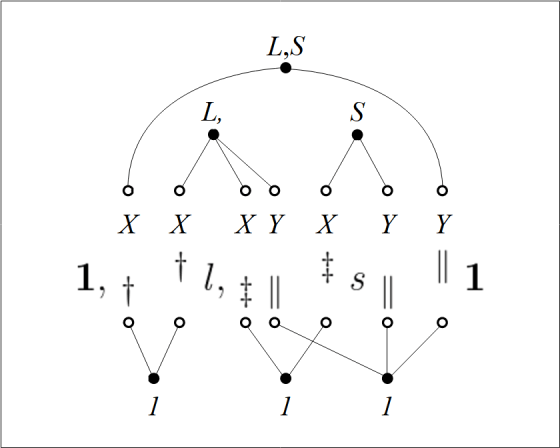

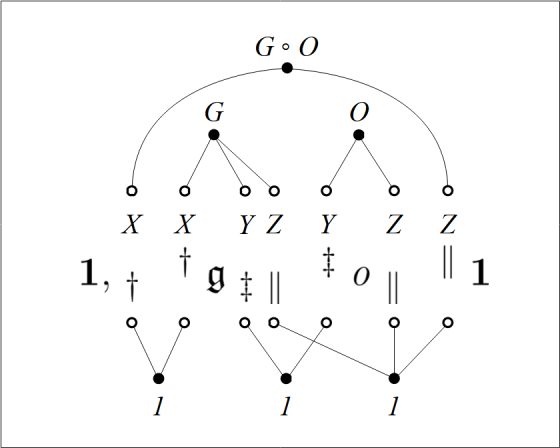

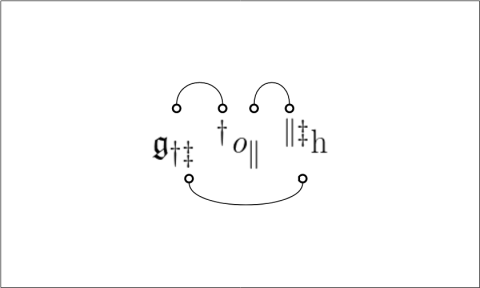

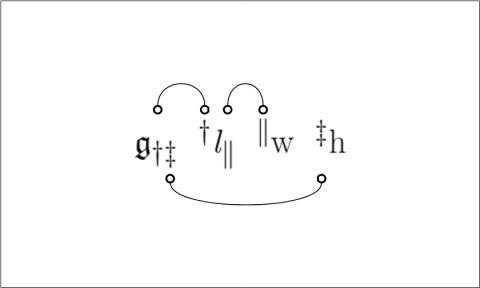

The conception of multiplication we have adopted is that of the application of one relation to another. …

Even ordinary numerical multiplication involves the same idea, for  is a pair of triplets, and

is a pair of triplets, and  is a triplet of pairs, where “triplet of” and “pair of” are evidently relatives.

is a triplet of pairs, where “triplet of” and “pair of” are evidently relatives.

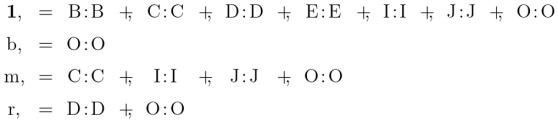

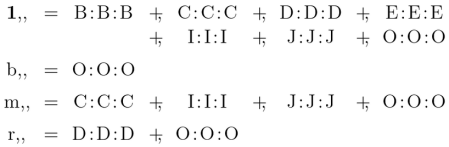

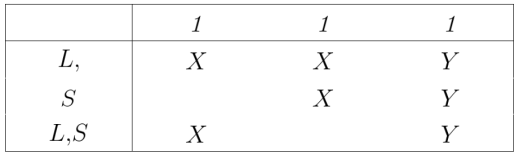

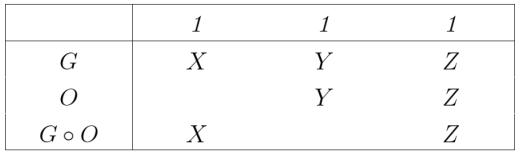

If we have an equation of the form

and there are just as many  ’s per

’s per  as there are, per things, things of the universe, then we have also the arithmetical equation,

as there are, per things, things of the universe, then we have also the arithmetical equation,

![[x][y] ~=~ [z].](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Bx%5D%5By%5D+%7E%3D%7E+%5Bz%5D.&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

For instance, if our universe is perfect men, and there are as many teeth to a Frenchman (perfect understood) as there are to any one of the universe, then

![[\mathit{t}][\mathrm{f}] ~=~ [\mathit{t}\mathrm{f}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cmathit%7Bt%7D%5D%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bf%7D%5D+%7E%3D%7E+%5B%5Cmathit%7Bt%7D%5Cmathrm%7Bf%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

holds arithmetically.

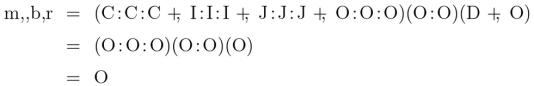

So if men are just as apt to be black as things in general,

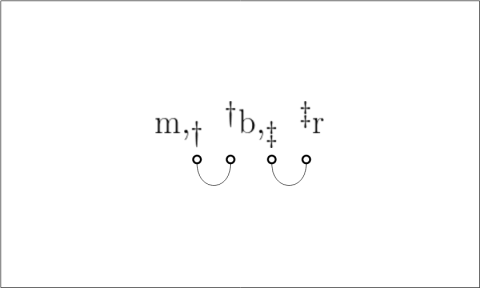

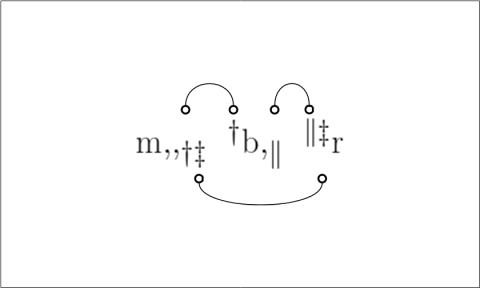

![[\mathrm{m,}][\mathrm{b}] ~=~ [\mathrm{m,}\mathrm{b}],](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bm%2C%7D%5D%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bb%7D%5D+%7E%3D%7E+%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bm%2C%7D%5Cmathrm%7Bb%7D%5D%2C&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

where the difference between ![[\mathrm{m}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bm%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![[\mathrm{m,}]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cmathrm%7Bm%2C%7D%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) must not be overlooked.

must not be overlooked.

It is to be observed that

![[\mathit{1}] ~=~ \mathfrak{1}.](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cmathit%7B1%7D%5D+%7E%3D%7E+%5Cmathfrak%7B1%7D.&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

Boole was the first to show this connection between logic and probabilities. He was restricted, however, to absolute terms. I do not remember having seen any extension of probability to relatives, except the ordinary theory of expectation.

Our logical multiplication, then, satisfies the essential conditions of multiplication, has a unity, has a conception similar to that of admitted multiplications, and contains numerical multiplication as a case under it.

(Peirce, CP 3.76)

Resources

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)