Peirce’s 1870 “Logic of Relatives” • Comment 11.13

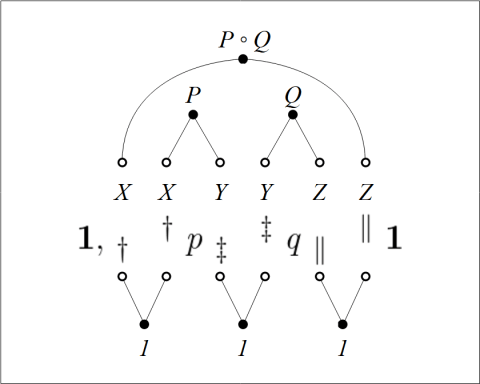

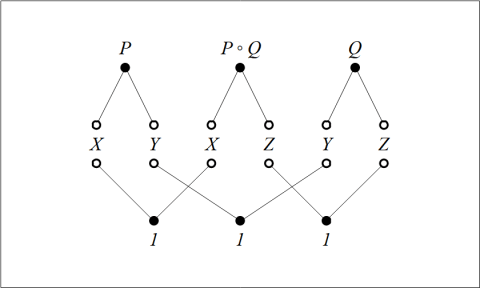

As we make our way toward the foothills of Peirce’s 1870 Logic of Relatives there are several pieces of equipment we must not leave the plains without, namely, the utilities variously known as arrows, morphisms, homomorphisms, structure-preserving maps, among other names, depending on the altitude of abstraction we happen to be traversing at the moment in question. As a moderate to middling but not too beaten track, let’s examine a few ways of defining morphisms that will serve us in the present discussion.

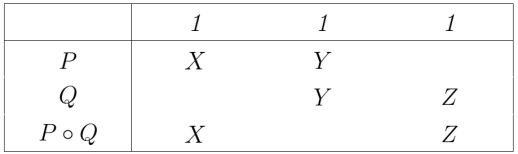

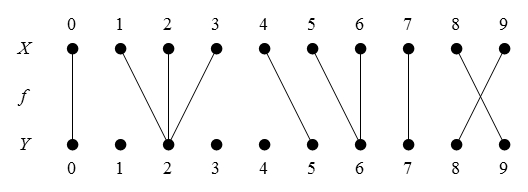

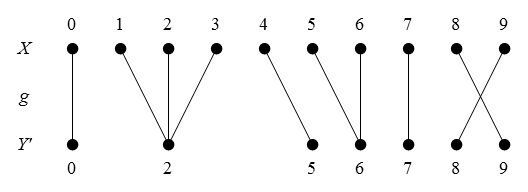

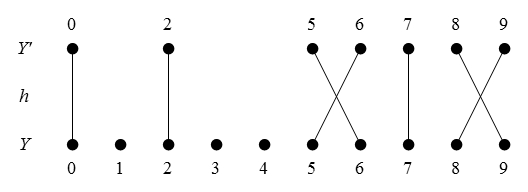

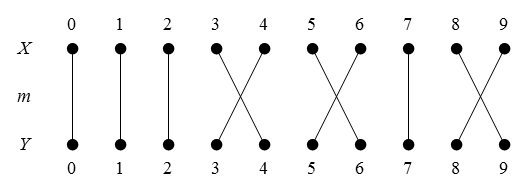

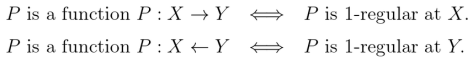

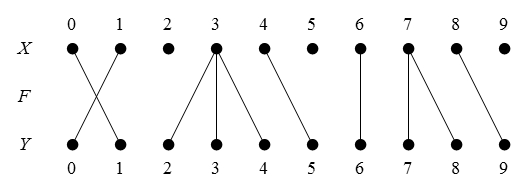

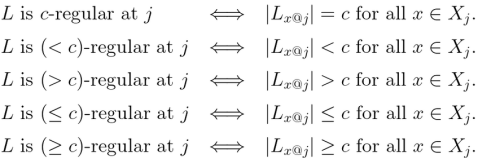

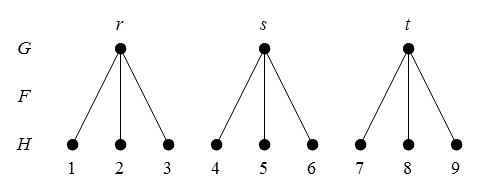

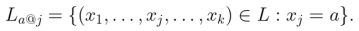

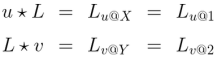

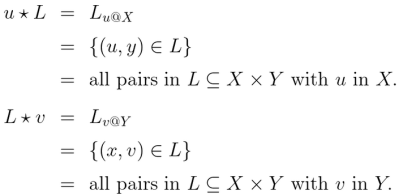

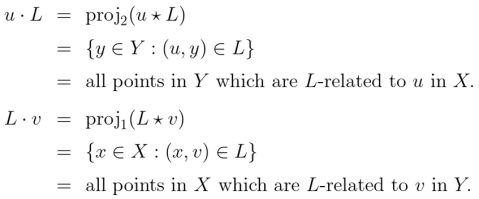

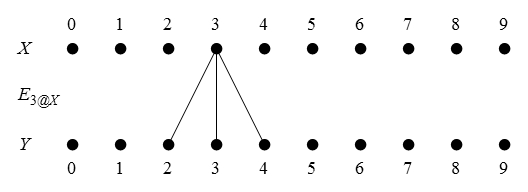

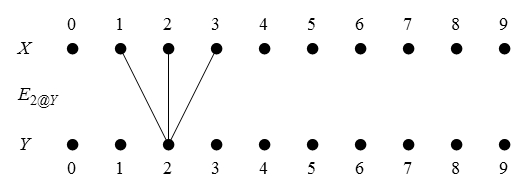

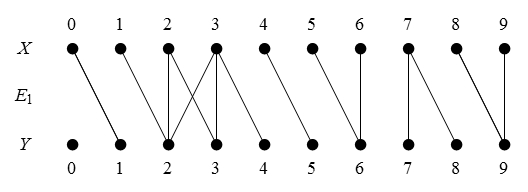

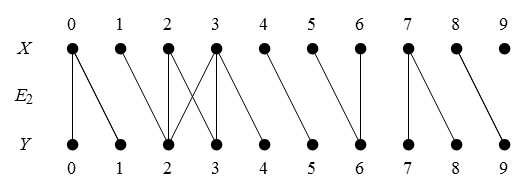

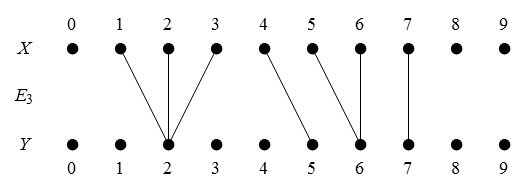

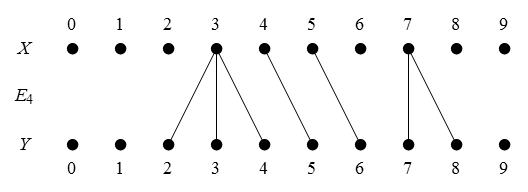

Suppose we are given three functions satisfying the following conditions.

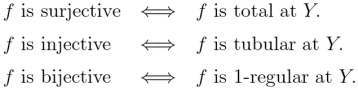

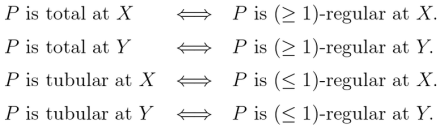

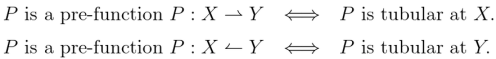

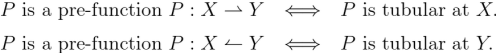

Our sagittarian leitmotif can be rubricized in the following slogan.

The J-image of the L-product is the K-product of the J-images.

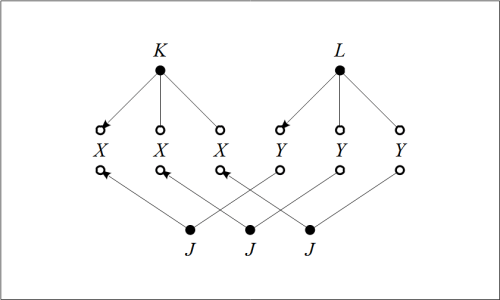

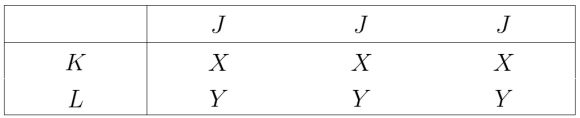

Figure 47 presents us with a picture of the situation in question.

Table 48 gives the constraint matrix version of the same thing.

One way to read the Table is in terms of the informational redundancies it summarizes. For example, one way to read it says that satisfying the constraint in the row along with all the constraints in the

columns automatically satisfies the constraint in the

row. Quite by design, that is one way to understand the equation

Resources

- Peirce’s 1870 Logic of Relatives • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • References

- Logic Syllabus • Relational Concepts • Relation Theory • Relative Term

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)