Peirce’s 1870 “Logic of Relatives” • Comment 11.23

Peirce’s description of logical conjunction and conditional probability via the logic of relatives and the mathematics of relations is critical to understanding the relationship between logic and measurement, in effect, the qualitative and quantitative aspects of inquiry. To root that connection firmly in mind, I will try to sum up as succinctly as possible, in more current notation, the lesson we ought to take away from Peirce’s last “number of” example, since I know the account I have given so far may appear to have wandered widely.

NOF 4.3

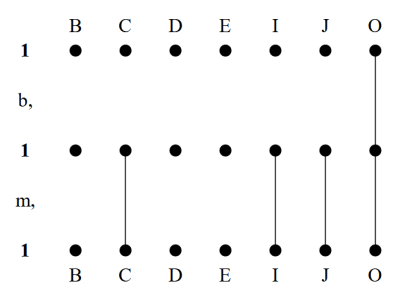

So if men are just as apt to be black as things in general,

where the difference between and

must not be overlooked.

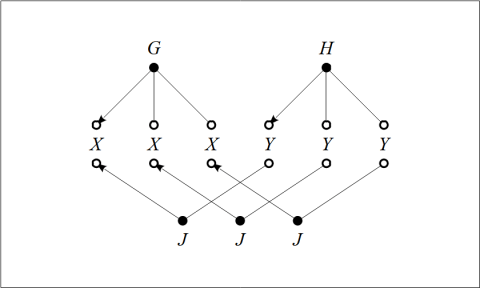

Viewed in different lights the formula presents itself as an aimed arrow, fair sampling, or statistical independence condition. The concept of independence was illustrated in the previous installment by means of a case where independence fails. The details of that counterexample are summarized below.

The condition that “men are just as apt to be black as things in general” is expressed in terms of conditional probabilities as which means that the probability of the event

given the event

is equal to the unconditional probability of the event

In the Othello example it is enough to observe that while

in order to recognize the bias or dependency of the sampling map.

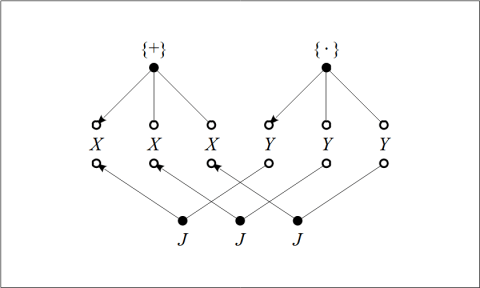

The reduction of a conditional probability to an absolute probability, as is one of the ways we come to recognize the condition of independence,

via the definition of conditional probability,

By way of recalling the derivation, the definition of conditional probability plus the independence condition yields the following sequence of equations.

As Hamlet discovered, there’s a lot to be learned from turning a crank.

Resources

- Peirce’s 1870 Logic of Relatives • Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • References

- Logic Syllabus • Relational Concepts • Relation Theory • Relative Term

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form (1) (2) • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)