Peirce’s 1870 “Logic of Relatives” • Comment 9.4

Boole rationalizes the properties of what we now call boolean multiplication, roughly equivalent to logical conjunction, by means of his concept of selective operations. Peirce, in his turn, taking a radical step of analysis which has seldom been recognized for what it would lead to, does not consider this multiplication a fundamental operation, but derives it as a by-product of relative multiplication by a comma relative. In this way Peirce makes logical conjunction a special case of relative composition.

This opens up a wide field of inquiry, the operational significance of logical terms, but it will be best to advance bit by bit and to lean on simple examples.

Back to Venice and the close-knit party of absolutes and relatives we entertained when last stopping there.

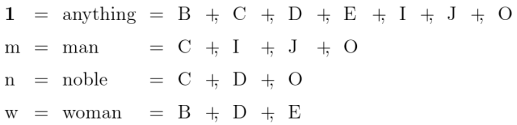

Here is the list of absolute terms we had been considering before:

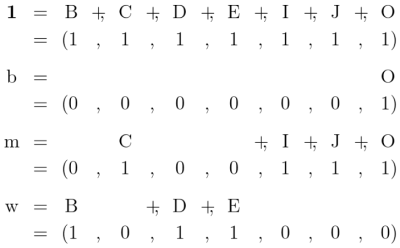

Here is the list of comma inflexions or diagonal extensions of those terms:

One observes the diagonal extension of is the same thing as the identity relation

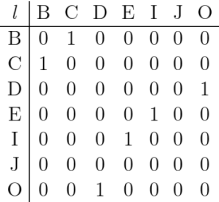

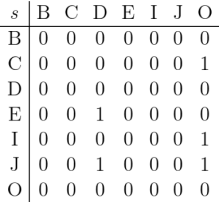

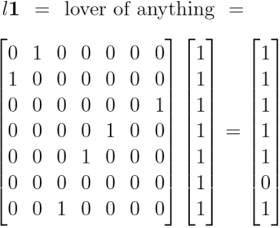

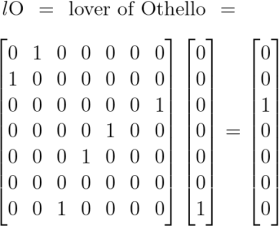

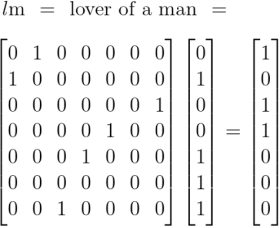

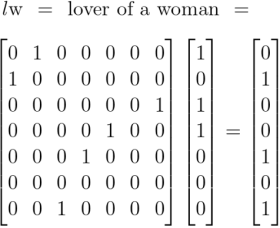

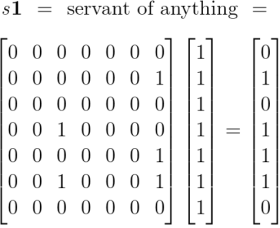

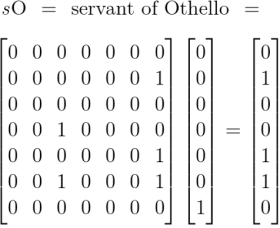

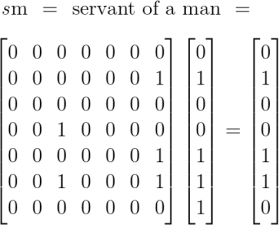

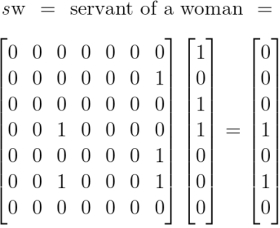

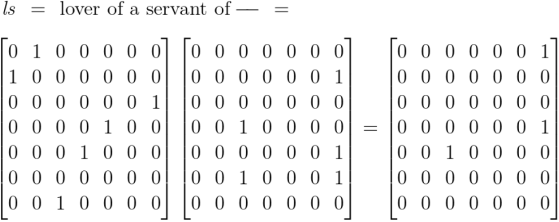

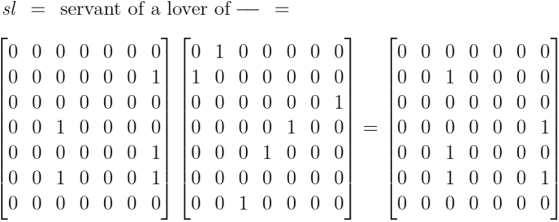

Earlier we computed the following products, obtained by applying the diagonal extensions of absolute terms to the same set of absolute terms.

From that we take our first clue why the commutative law holds for logical conjunction. More in the way of practical insight could be had by working systematically through the collection of products generated by the operational means at hand, namely, the products obtained by appending a comma to each of the terms then applying the resulting relatives to those selfsame terms again.

Before we venture into that territory, however, let us equip our intuitions with the forms of graphical and matrical representation which served us so well in our previous adventures.

Resources

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: FB | Peirce Matters • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)