Re: Peirce List • Tom Gollier

At this point in our paper, Sue and I had already introduced the rudiments of sign relations, as far as the common notions and continuities of thought underpinning the semiotic bridge from Aristotle to Peirce might be teased out, and we turned to the task of tracing the role of sign relations in the workings of a fully filled out inquiry process, with all its abductive, deductive, and inductive faculties intact.

The relation between theories of signs and theories of inquiry, as we find them in Aristotle, or Peirce, or name your favorite, or as we must find them at “the end of all our exploring”, are some of the things I’m still trying to understand but I can’t let my need to think I know much prevent me from learning more.

At any rate we do have a general outline from Peirce of how he thinks one cycle of inquiry goes, so what we tried to do in this case was to fit the semiotic roles into that hopper as best we could and see how far that afforded us any guidance in understanding the dynamics of Dewey’s story.

With that pre-ramble …

Any realistic practical situation will involve all sorts of objects, passed, pressing, and prospective. Practical applications force us at any given moment to deal with an object domain that is a collection of many objects

Objects and objectives can be complex. Objects can have sub-objects and super-objects. Objectives can have sub-objectives and super-objectives, though we usually speak of goals and subgoals then. The same goes for signs and interpretant signs, of course, which is what syntactic analysis and conceptual analysis are all about.

That overarching interest in practical applications is one of the reasons I’m always harping on the extensional formulation of a sign relation as a set where

are sets of many elements. The object domain

is very like the universe of discourse in ordinary logic, while

and

are the systems of signs, public or private or whatever, that we use to talk and think about our present object domain.

So …

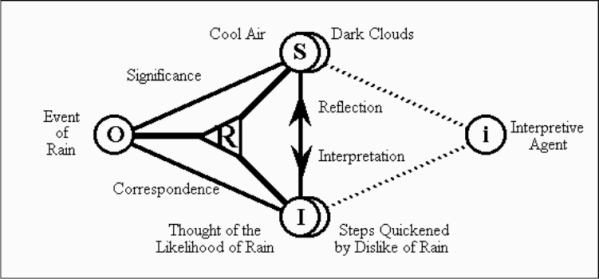

What makes the likelihood of rain a semiotic object in Dewey’s story is simply the fact that the ambulator interprets the cooling air as a sign of it. We know the interpreter interprets the sign as a sign of that object by virtue of the fact that he forms an interpretent sign, the thought of the likelihood of rain, in his mind.