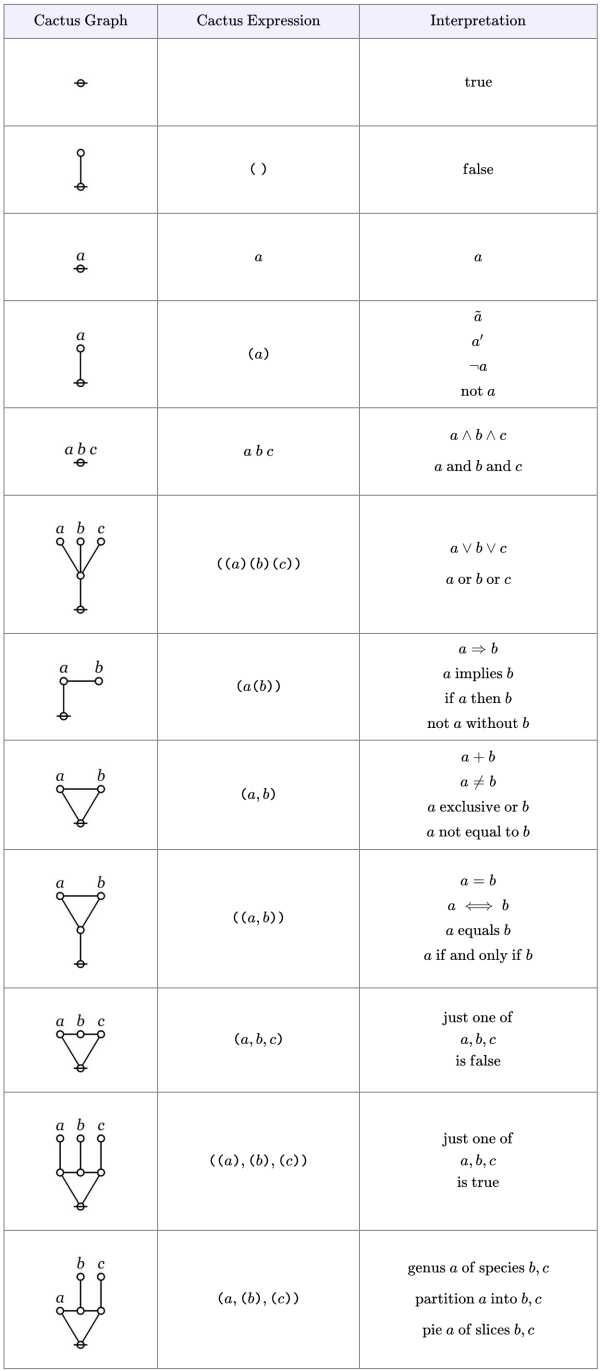

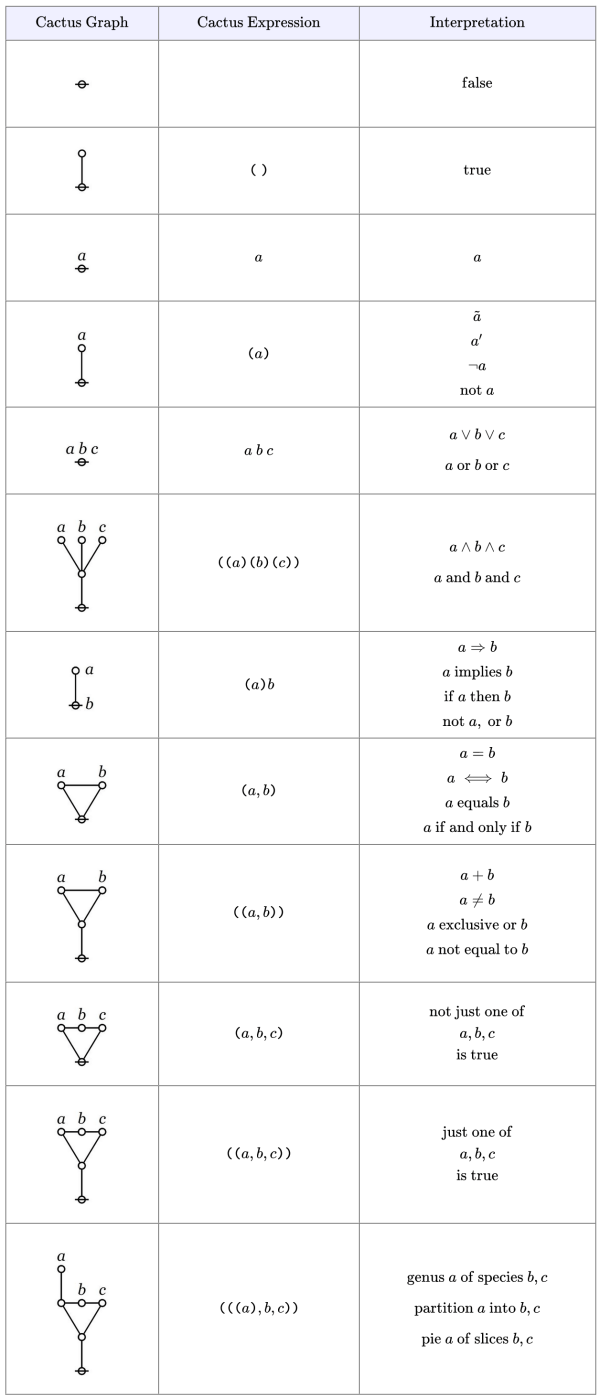

We have seen how to take an abstract logical graph of a sort a person might have in mind to represent a logical state of affairs and translate it into a string of characters a computer can translate into a concrete data structure.

Now we look a little more closely at the finer details of those data structures, as they work out in this particular sequence of representations.

Parsing Logical Graphs

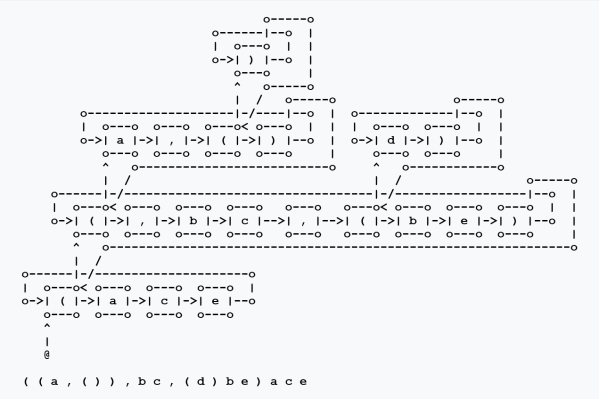

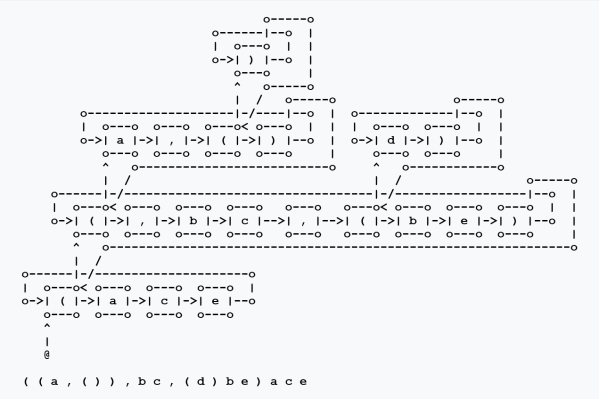

It is possible to write a program that parses cactus expressions into reasonable facsimiles of cactus graphs as pointer structures in computer memory, making edges correspond to addresses and nodes correspond to records. I did just that in the early forerunners of the present program, but it turned out to be a more robust strategy in the long run, despite the need for additional nodes at the outset, to implement a more articulate but more indirect parsing algorithm, one in which the punctuation marks are not just tacitly converted to addresses in passing, but instead recorded as nodes in roughly the same way as the ordinary identifiers, or paints.

Figure 3 illustrates the type of parsing paradigm used by the program, showing the pointer graph structure obtained by parsing the cactus expression in Figure 2. A traversal of this graph naturally reconstructs the cactus string that parses into it.

The pointer graph in Figure 3, namely, the parse graph of a cactus expression, is the sort of thing we’ll probably not be able to resist calling a cactus graph, for all the looseness of that manner of speaking, but we should keep in mind its level of abstraction lies a step further in the direction of a concrete implementation than the last thing we called by that name. While we have them before our mind’s eyes, there are several other distinctive features of cactus parse graphs we ought to notice before moving on.

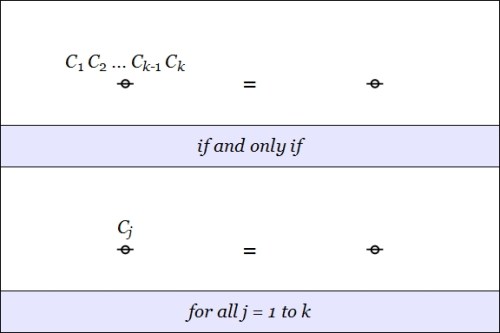

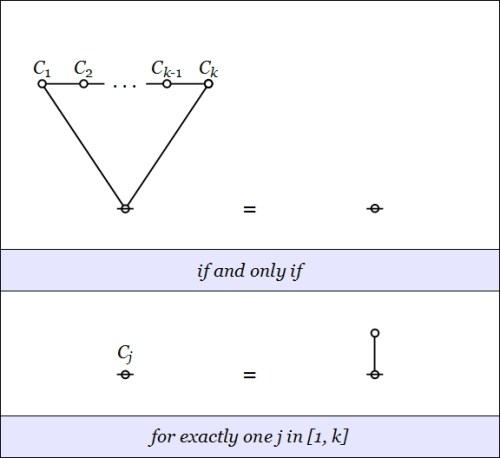

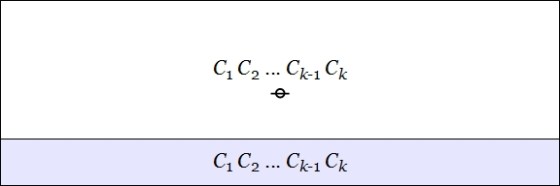

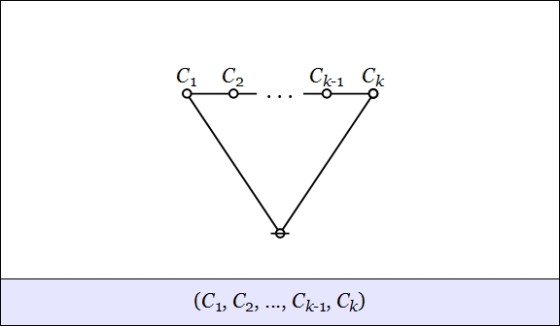

In terms of idea-form structures, a cactus parse graph begins with a root idea pointing into a by‑cycle of forms, each of whose sign fields bears either a paint, in other words, a direct or indirect identifier reference, or an opening left parenthesis indicating a link to a subtended lobe of the cactus.

A lobe springs from a form whose sign field bears a left parenthesis. That stem form has an on idea pointing into a by‑cycle of forms, exactly one of which has a sign field bearing a right parenthesis. That last form has an on idea pointing back to the form bearing the initial left parenthesis.

In the case of a lobe, aside from the single form bearing the closing right parenthesis, the by‑cycle of a lobe may list any number of forms, each of whose sign fields bears either a comma, a paint, or an opening left parenthesis signifying a link to a more deeply subtended lobe.

Just to draw out one of the implications of this characterization and to stress the point of it, the root node can be painted and bear many lobes, but it cannot be segmented, that is, the by‑cycle corresponding to the root node can bear no commas.

Resources

cc: Peirce List • (1) • (2)