Re: Cybernetics • Cliff Joslyn

- CJ:

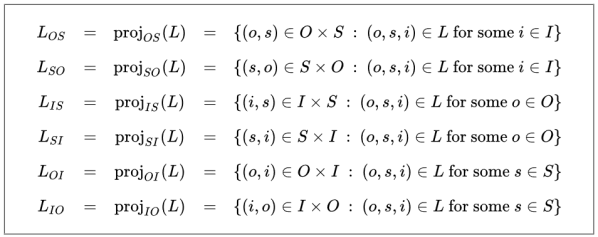

- For a given arbitrary triadic relation

(let’s say that

and

are all finite, non‑empty sets), I’m interested to understand what additional axioms you’re saying are necessary and sufficient to make

a sign relation. I checked Sign Relations • Definition, but it wasn’t obvious, or at least, not formalized.

Dear Cliff,

Peirce claims a definition of logic as formal semiotic and goes on to define a sign in terms of its relation to its interpretant sign and its object.

For ease of reference, here’s the cited paragraph again.

Logic will here be defined as formal semiotic. A definition of a sign will be given which no more refers to human thought than does the definition of a line as the place which a particle occupies, part by part, during a lapse of time. Namely, a sign is something, A, which brings something, B, its interpretant sign determined or created by it, into the same sort of correspondence with something, C, its object, as that in which itself stands to C. It is from this definition, together with a definition of “formal”, that I deduce mathematically the principles of logic. I also make a historical review of all the definitions and conceptions of logic, and show, not merely that my definition is no novelty, but that my non‑psychological conception of logic has virtually been quite generally held, though not generally recognized. (C.S. Peirce, NEM 4, 20–21).

Let me cut to the chase and say what I see in that passage. Peirce draws our attention to a category of mathematical structures of use in understanding various domains of complex phenomena by capturing aspects of objective structure immanent in those domains.

The domains of complex phenomena of interest to logic in its broadest sense encompass all that appears on the discourse side of any universe of discourse we happen to discuss. That’s a big enough sky for anyone to live under, but for the moment I am focusing on the ways we transform signs in activities like communication, computation, inquiry, learning, proof, and reasoning in general. I’m especially focused on the ways we do now and may yet use computation to advance the other pursuits on that list.

To be continued …

Reference

- Charles S. Peirce (1902), “Parts of Carnegie Application” (L 75), in Carolyn Eisele (ed., 1976), The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce, vol. 4, 13–73. Online.

Sources

- C.S. Peirce • On the Definition of Logic

- C.S. Peirce • Logic as Semiotic

- C.S. Peirce • Objective Logic

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Ontolog Forum

cc: FB | Semeiotics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science