Re: Peirce List • Kaina Stoicheia and the Symbol Grounding Problem

Re: Jerry Chandler • Christophe Menant • Jon Awbrey • Christophe Menant

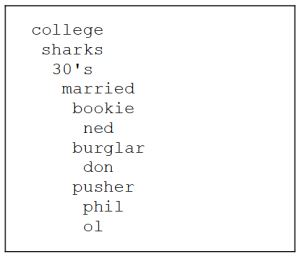

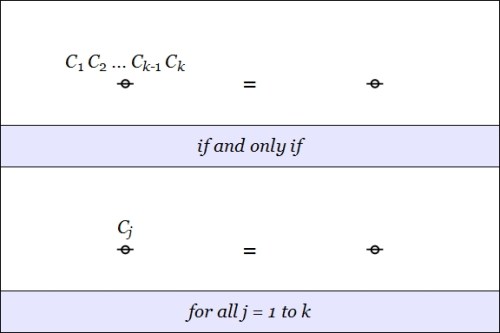

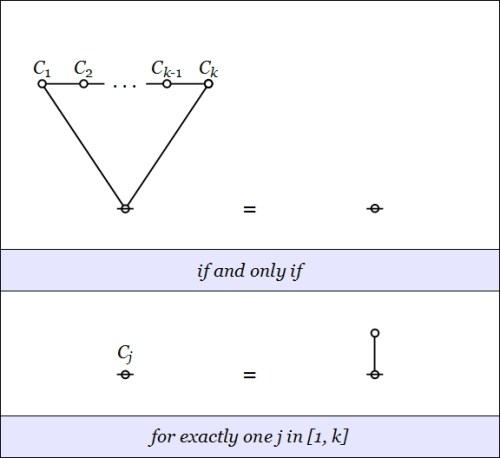

The system‑theoretic concept of constraint is one that unifies a manifold of other notions — definition, determination, habit, information, law, predicate, regularity, and so on. Indeed, it is often the best way to understand the entire complex of concepts.

Entwined with the concept of constraint is the concept of information, the power signs bear to reduce uncertainty and advance inquiry. Asking what consequences those ideas have for Peirce’s theory of triadic sign relations led me some years ago to the thoughts recorded on the following page.

Here I am thinking of the concept of constraint that constitutes one of the fundamental ideas of classical cybernetics and mathematical systems theory.

For example, here is how W. Ross Ashby introduces the concept of constraint in his Introduction to Cybernetics (1956).

A most important concept, with which we shall be much concerned later, is that of constraint. It is a relation between two sets, and occurs when the variety that exists under one condition is less than the variety that exists under another. Thus, the variety of the human sexes is 1 bit; if a certain school takes only boys, the variety in the sexes within the school is zero; so as 0 is less than 1, constraint exists. (1964 ed., p. 127).

At its simplest, then, constraint is an aspect of the subset relation.

The objective of an agent, organism, or similar regulator is to keep within its viable region, a particular subset of its possible state space. That is the constraint of primary interest to the agent.

Reference

- Ashby, W.R. (1956), Introduction to Cybernetics, Methuen, London, UK.

Resources

cc: FB | Inquiry Driven Systems • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science