A differential propositional calculus is a propositional calculus extended by a set of terms for describing aspects of change and difference, for example, processes taking place in a universe of discourse or transformations mapping a source universe to a target universe.

Casual Introduction

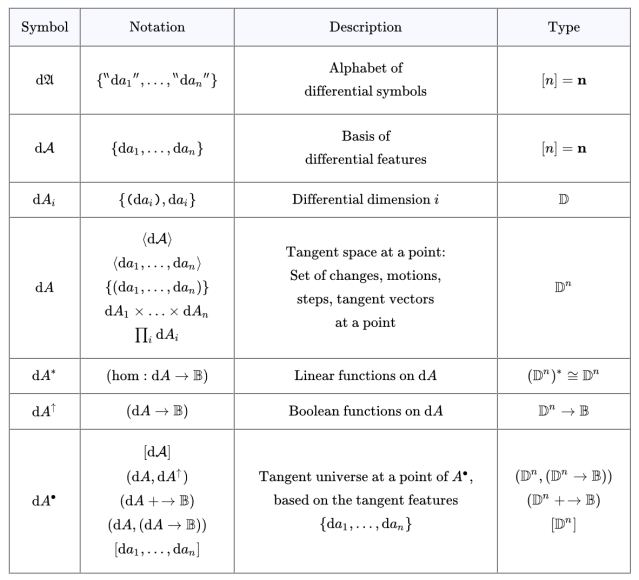

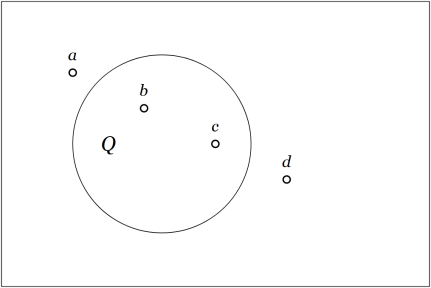

Consider the situation represented by the venn diagram in Figure 1.

The area of the rectangle represents a universe of discourse,  The universe under discussion may be a population of individuals having various additional properties or it may be a collection of locations occupied by various individuals. The area of the “circle” represents the individuals having the property

The universe under discussion may be a population of individuals having various additional properties or it may be a collection of locations occupied by various individuals. The area of the “circle” represents the individuals having the property  or the locations in the corresponding region

or the locations in the corresponding region  Four individuals,

Four individuals,  are singled out by name. It happens that

are singled out by name. It happens that  and

and  currently reside in region

currently reside in region  while

while  and

and  do not.

do not.

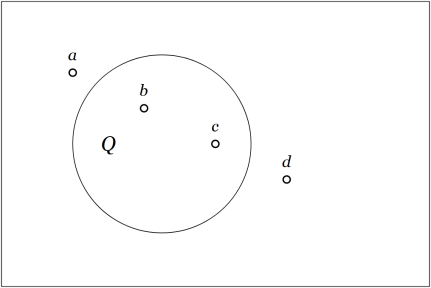

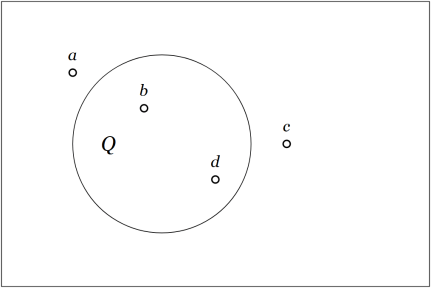

Now consider the situation represented by the venn diagram in Figure 2.

Figure 2 differs from Figure 1 solely in the circumstance that the object  is outside the region

is outside the region  while the object

while the object  is inside the region

is inside the region  So far, nothing says our encountering these Figures in this order is other than purely accidental but if we interpret this sequence of frames as a “moving picture” representation of their natural order in a temporal process then it would be natural to suppose

So far, nothing says our encountering these Figures in this order is other than purely accidental but if we interpret this sequence of frames as a “moving picture” representation of their natural order in a temporal process then it would be natural to suppose  and

and  have remained as they were with regard to the quality

have remained as they were with regard to the quality  while

while  and

and  have changed their standings in that respect. In particular,

have changed their standings in that respect. In particular,  has moved from the region where

has moved from the region where  is true to the region where

is true to the region where  is false while

is false while  has moved from the region where

has moved from the region where  is false to the region where

is false to the region where  is true.

is true.

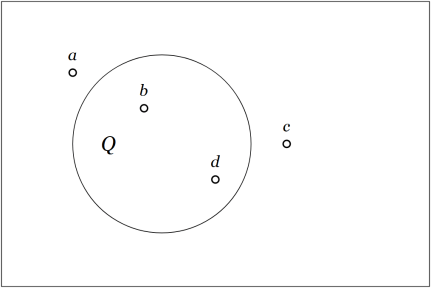

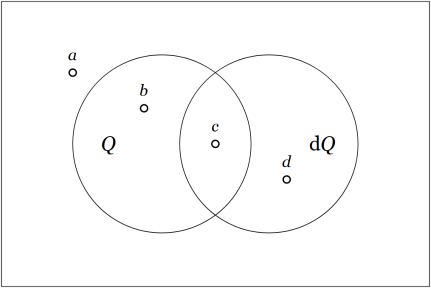

Figure 3 returns to the situation in Figure 1, but this time interpolates a new quality specifically tailored to account for the relation between Figure 1 and Figure 2.

This new quality,  is an example of a differential quality, since its absence or presence qualifies the absence or presence of change occurring in another quality. As with any other quality, it is represented in the venn diagram by means of a “circle” distinguishing two halves of the universe of discourse, in this case, the portions of

is an example of a differential quality, since its absence or presence qualifies the absence or presence of change occurring in another quality. As with any other quality, it is represented in the venn diagram by means of a “circle” distinguishing two halves of the universe of discourse, in this case, the portions of  outside and inside the region

outside and inside the region

Figure 1 represents a universe of discourse,  together with a basis of discussion,

together with a basis of discussion,  for expressing propositions about the contents of that universe. Once the quality

for expressing propositions about the contents of that universe. Once the quality  is given a name, say, the symbol

is given a name, say, the symbol  we have the basis for a formal language specifically cut out for discussing

we have the basis for a formal language specifically cut out for discussing  in terms of

in terms of  This language is more formally known as the propositional calculus with alphabet

This language is more formally known as the propositional calculus with alphabet

In the context marked by  and

and  there are just four distinct pieces of information which can be expressed in the corresponding propositional calculus, namely, the constant proposition

there are just four distinct pieces of information which can be expressed in the corresponding propositional calculus, namely, the constant proposition  the negative proposition

the negative proposition  the positive proposition

the positive proposition  and the constant proposition

and the constant proposition

For example, referring to the points in Figure 1, the constant proposition  holds of no points, the negative proposition

holds of no points, the negative proposition  holds of

holds of  and

and  the positive proposition

the positive proposition  holds of

holds of  and

and  and the constant proposition

and the constant proposition  holds of all points in the sample.

holds of all points in the sample.

Figure 3 extends the basis of description for the space  to a set of two qualities

to a set of two qualities  and the corresponding terms of description to an alphabet of two symbols

and the corresponding terms of description to an alphabet of two symbols

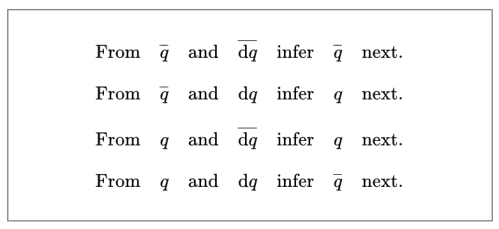

Any propositional calculus over two basic propositions allows for the expression of sixteen propositions all together. Salient among those propositions in the present setting are the four which single out the individual sample points at the initial moment of observation. Table 4 lists the initial state descriptions, using overlines to express logical negations.

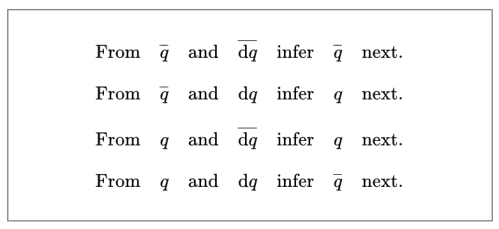

Table 5 shows the rules of inference responsible for giving the differential quality  its meaning in practice.

its meaning in practice.

Resources

cc: Cybernetics • Ontolog Forum • Peirce List • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

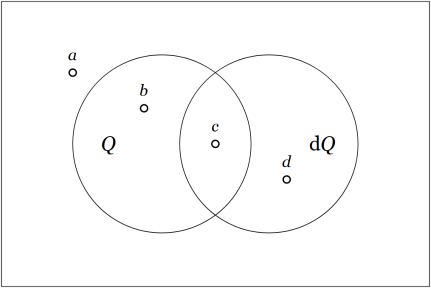

supplies the groundwork for any number of further extensions, beginning with the first order differential extension

The construction of

can be described in the following stages.

is extended by a first order differential alphabet

resulting in a first order extended alphabet

defined as follows.

is extended by a first order differential basis

resulting in a first order extended basis

defined as follows.

is extended by a first order differential space or tangent space

at each point of

resulting in a first order extended space or tangent bundle space

defined as follows.

is extended by a first order differential universe or tangent universe

at each point of

resulting in a first order extended universe or tangent bundle universe

defined as follows.

a type defined as follows.

and the first order differential propositions

we arrive at the foothills of differential logic.