Triadic Relations • Examples from Semiotics

The study of signs — the full variety of significant forms of expression — in relation to all the affairs signs are significant of, and in relation to all the beings signs are significant to, is known as semiotics or the theory of signs. As described, semiotics treats of a -place relation among signs, their objects, and their interpreters.

The term semiosis refers to any activity or process involving signs. Studies of semiosis focusing on its abstract form are not concerned with every concrete detail of the entities acting as signs, as objects, or as agents of semiosis, but only with the most salient patterns of relationship among those three roles. In particular, the formal theory of signs does not consider all the properties of the interpretive agent but only the more striking features of the impressions signs make on a representative interpreter. From a formal point of view this impact or influence may be treated as just another sign, called the interpretant sign, or the interpretant for short. A triadic relation of this type, among objects, signs, and interpretants, is called a sign relation.

For example, consider the aspects of sign use involved when two people, say Ann and Bob, use their own proper names, “Ann” and “Bob”, along with the pronouns, “I” and “you”, to refer to themselves and each other. For brevity, these four signs may be abbreviated to the set The abstract consideration of how

and

use this set of signs leads to the contemplation of a pair of triadic relations, the sign relations

and

reflecting the differential use of these signs by

and

respectively.

Each of the sign relations and

consists of eight triples of the form

where the object

belongs to the object domain

the sign

belongs to the sign domain

the interpretant sign

belongs to the interpretant domain

and where it happens in this case that

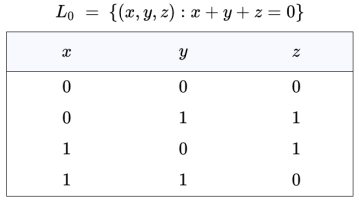

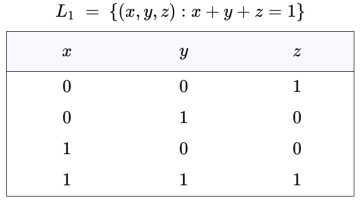

The union

is often referred to as the syntactic domain, but in this case

The set-up so far is summarized as follows:

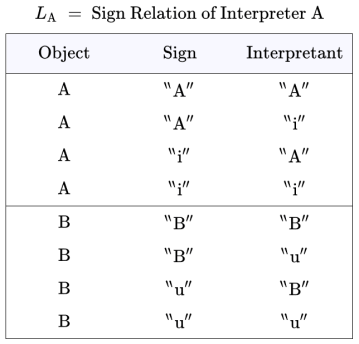

The relation is the following set of eight triples in

The triples in represent the way interpreter

uses signs. For example, the presence of

in

says

uses

to mean the same thing

uses

to mean, namely,

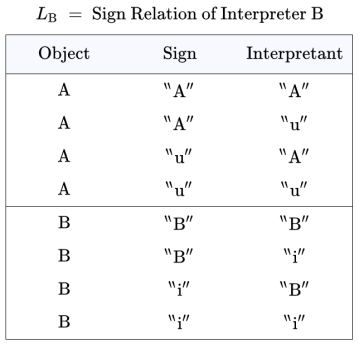

The relation is the following set of eight triples in

The triples in represent the way interpreter

uses signs. For example, the presence of

in

says

uses

to mean the same thing

uses

to mean, namely,

The triples in the relations and

are conveniently arranged in the form of relational data tables, as shown below.

Document History

Portions of the above article were adapted from the following sources under the GNU Free Documentation License, under other applicable licenses, or by permission of the copyright holders.

- Triadic Relation • OEIS Wiki

- Triadic Relation • InterSciWiki

- Triadic Relation • MyWikiBiz

- Triadic Relation • Wikiversity

- Triadic Relation • Wikipedia

cc: Category Theory • Cybernetics (1) (2) • Ontolog (1) (2)

cc: Structural Modeling (1) (2) • Systems Science (1) (2)

cc: FB | Relation Theory • Laws of Form • Peirce List (1) (2)