Truth Theories

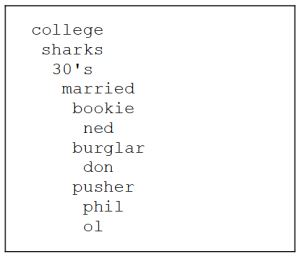

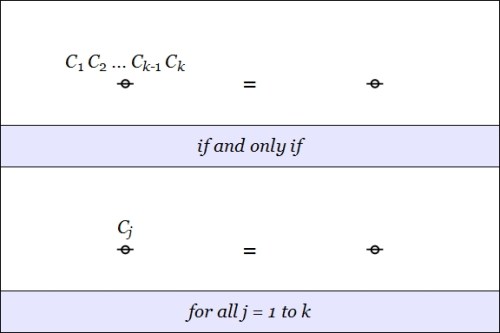

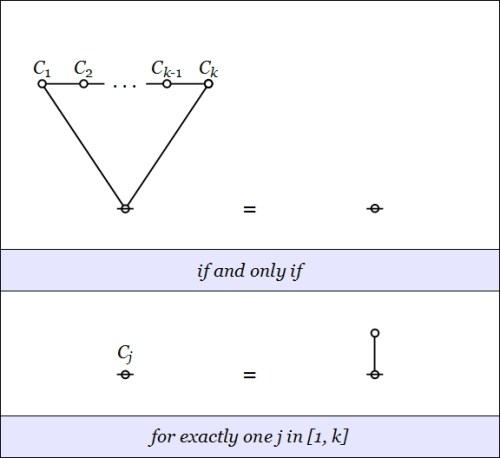

Theories of truth may be described according to several dimensions of description affecting the character of the predicate “true”. The truth predicates used in different theories may be classified according to the number of things which have to be taken into account in order to evaluate the truth of a sign, counting the sign itself as the first thing. The number of dimensions is sometimes called the arity or adicity of the truth predicate.

- A truth predicate is monadic if it applies to its main subject, typically a concrete representation or its abstract content, independently of reference to anything else. In that case one may think of a truth bearer as being true in and of itself.

- A truth predicate is dyadic if it applies to its main subject only in reference to something else, a second subject. Most commonly, the ancillary subject is either an object, an interpreter, or a language to which the representation bears a specified relation.

- A truth predicate is triadic if it applies to its main subject only in reference to a second and a third subject. For example, in a pragmatic theory of truth one has to specify both the object of the sign and either its interpreter or another sign called its interpretant. In that case, one says the sign is true “of” its object “to” its interpreting agent or sign.

There are practical considerations we need to keep in mind when contemplating such radically simple schemes of classification. Real‑world practice seldom presents us with pure cases and ideal types. There are many settings where it is useful to speak of a truth theory as “almost” -adic or to say it “would be”

-adic if certain details are abstracted away and neglected in a particular context of discussion. That said, given the generic division of truth predicates according to their dimensionality, further species may be differentiated within each genus according to a number of more refined features.

The truth predicate in a correspondence theory of truth tells of a relation between representations and objective states of affairs and is therefore expressed by a dyadic predicate. In general terms, one says a representation is true of an objective situation, more briefly, a sign is true of an object. The nature of the correspondence may vary from theory to theory in this family. The correspondence can be fairly arbitrary or it can take on the character of an analogy, an icon, or a morphism, where a representation is rendered true of its object by the existence of corresponding elements and a similar structure.

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Pragmatic Maxim

- Truth Theory

- Pragmatic Theory Of Truth

- Correspondence Theory Of Truth

cc: FB | Inquiry Driven Systems • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science