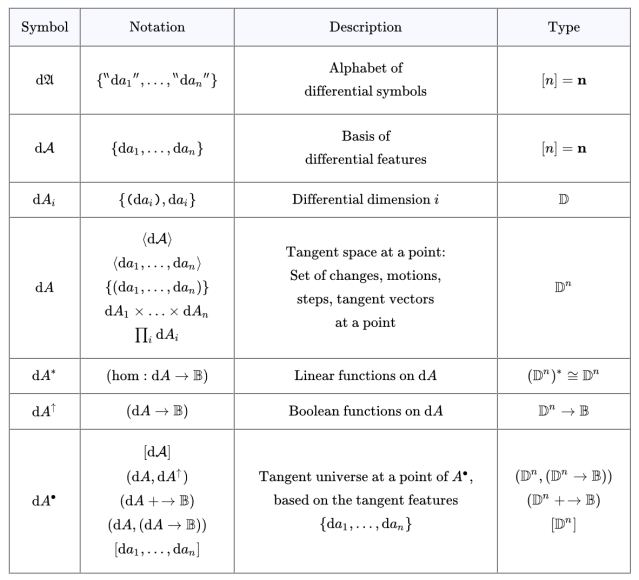

Differential Propositions • Tangent Spaces

The tangent space to at one of its points

sometimes written

takes the form

Strictly speaking, the name cotangent space is probably more correct for this construction but since we take up spaces and their duals in pairs to form our universes of discourse it allows our language to be pliable here.

Proceeding as we did with the base space the tangent space

at a point of

may be analyzed as the following product of distinct and independent factors.

Each factor is a set consisting of two differential propositions,

where

is a proposition with the logical value of

Each component

has the type

operating under the ordered correspondence

A measure of clarity is achieved, however, by acknowledging the differential usage with a superficially distinct type

whose sense may be indicated as follows.

Viewed within a coordinate representation, spaces of type and

may appear to be identical sets of binary vectors, but taking a view at that level of abstraction would be like ignoring the qualitative units and the diverse dimensions that distinguish position and momentum, or the different roles of quantity and impulse.

Resources

cc: FB | Differential Logic • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs (1) (2) • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science