Logical graphs are next presented as a formal system by going back to the initial elements and developing their consequences in a systematic manner.

Formal Development

Logical Graphs • First Impressions gives an informal introduction to the initial elements of logical graphs and hopefully supplies the reader with an intuitive sense of their motivation and rationale.

The next order of business is to give the precise axioms used to develop the formal system of logical graphs. The axioms derive from C.S. Peirce’s various systems of graphical syntax via the calculus of indications described in Spencer Brown’s Laws of Form. The formal proofs to follow will use a variation of Spencer Brown’s annotation scheme to mark each step of the proof according to which axiom is called to license the corresponding step of syntactic transformation, whether it applies to graphs or to strings.

Axioms

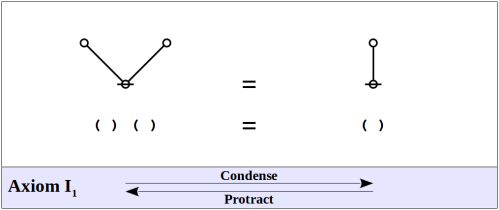

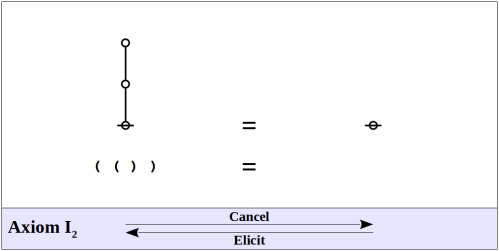

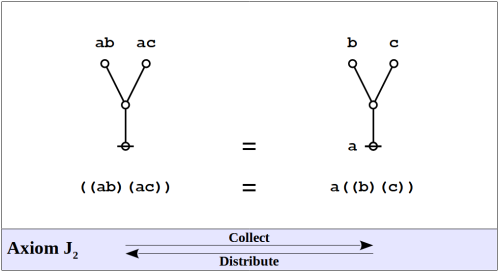

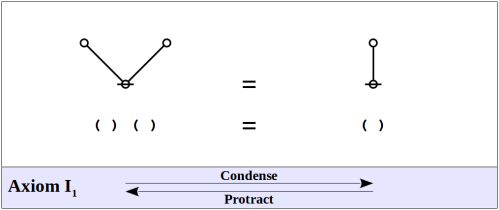

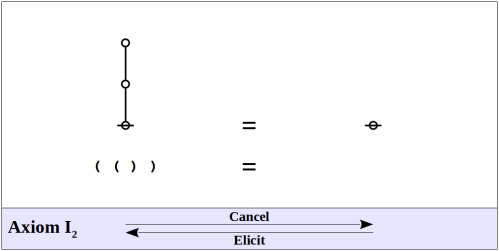

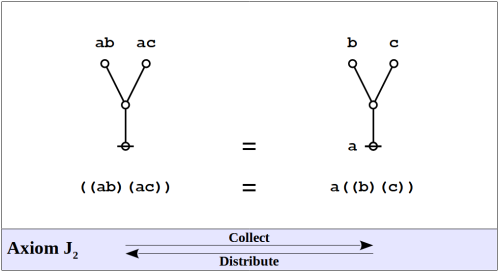

The formal system of logical graphs is defined by a foursome of formal equations, called initials when regarded purely formally, in abstraction from potential interpretations, and called axioms when interpreted as logical equivalences. There are two arithmetic initials and two algebraic initials, as shown below.

Arithmetic Initials

Algebraic Initials

Logical Interpretation

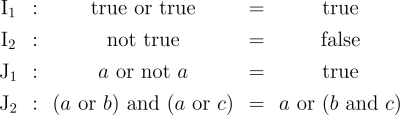

One way of assigning logical meaning to the initial equations is known as the entitative interpretation (En). Under En, the axioms read as follows.

![\begin{array}{ccccc} \mathrm{I_1} & : & \text{true} ~ \text{or} ~ \text{true} & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{I_2} & : & \text{not} ~ \text{true} & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_1} & : & a ~ \text{or} ~ \text{not} ~ a & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_2} & : & (a ~ \text{or} ~ b) ~ \text{and} ~ (a ~ \text{or} ~ c) & = & a ~ \text{or} ~ (b ~ \text{and} ~ c) \end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bccccc%7D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+a++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+b%29+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+c%29++%26+%3D+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%28b+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+c%29++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

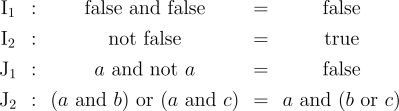

Another way of assigning logical meaning to the initial equations is known as the existential interpretation (Ex). Under Ex, the axioms read as follows.

![\begin{array}{ccccc} \mathrm{I_1} & : & \text{false} ~ \text{and} ~ \text{false} & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{I_2} & : & \text{not} ~ \text{false} & = & \text{true} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_1} & : & a ~ \text{and} ~ \text{not} ~ a & = & \text{false} \\[4pt] \mathrm{J_2} & : & (a ~ \text{and} ~ b) ~ \text{or} ~ (a\ \text{and}\ c) & = & a ~ \text{and} ~ (b ~ \text{or} ~ c) \end{array}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bccccc%7D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BI_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Btrue%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_1%7D++%26+%3A+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bnot%7D+%7E+a+++%26+%3D+%26+%5Ctext%7Bfalse%7D++%5C%5C%5B4pt%5D++%5Cmathrm%7BJ_2%7D++%26+%3A+%26+%28a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+b%29+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+%28a%5C+%5Ctext%7Band%7D%5C+c%29++%26+%3D+%26+a+%7E+%5Ctext%7Band%7D+%7E+%28b+%7E+%5Ctext%7Bor%7D+%7E+c%29++%5Cend%7Barray%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=1&c=20201002)

Equational Inference

All the initials  have the form of equations. This means the inference steps they license are reversible. The proof annotation scheme employed below makes use of double bars

have the form of equations. This means the inference steps they license are reversible. The proof annotation scheme employed below makes use of double bars  to mark this fact, though it will often be left to the reader to decide which of the two possible directions is the one required for applying the indicated axiom.

to mark this fact, though it will often be left to the reader to decide which of the two possible directions is the one required for applying the indicated axiom.

The actual business of proof is a far more strategic affair than the routine cranking of inference rules might suggest. Part of the reason for this lies in the circumstance that the customary types of inference rules combine the moving forward of a state of inquiry with the losing of information along the way that doesn’t appear immediately relevant, at least, not as viewed in the local focus and short run of the proof in question. Over the long haul, this has the pernicious side‑effect that one is forever strategically required to reconstruct much of the information one had strategically thought to forget at earlier stages of proof, where “before the proof started” can be counted as an earlier stage of the proof in view.

This is just one of the reasons it can be very instructive to study equational inference rules of the sort our axioms have just provided. Although equational forms of reasoning are paramount in mathematics, they are less familiar to the student of the usual logic textbooks, who may find a few surprises here.

Frequently Used Theorems

To familiarize ourselves with equational proofs in logical graphs let’s run though the proofs of a few basic theorems in the primary algebra.

C1. Double Negation Theorem

The first theorem goes under the names of Consequence 1 (C1), the double negation theorem (DNT), or Reflection.

The proof that follows is adapted from the one George Spencer Brown gave in his book Laws of Form and credited to two of his students, John Dawes and D.A. Utting.

C2. Generation Theorem

One theorem of frequent use goes under the nickname of the weed and seed theorem (WAST). The proof is just an exercise in mathematical induction, once a suitable basis is laid down, and it will be left as an exercise for the reader. What the WAST says is that a label can be freely distributed or freely erased anywhere in a subtree whose root is labeled with that label. The second in our list of frequently used theorems is in fact the base case of the weed and seed theorem. In Laws of Form it goes by the names of Consequence 2 (C2) or Generation.

Here is a proof of the Generation Theorem.

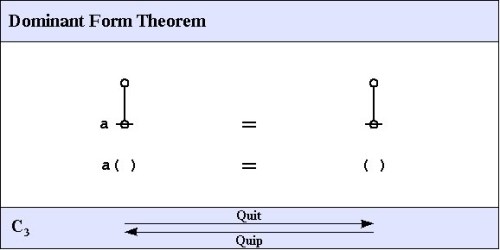

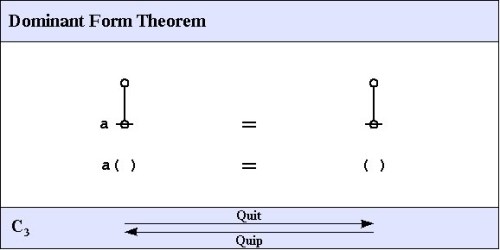

C3. Dominant Form Theorem

The third of the frequently used theorems of service to this survey is one Spencer Brown annotates as Consequence 3 (C3) or Integration. A better mnemonic might be dominance and recession theorem (DART), but perhaps the brevity of dominant form theorem (DFT) is sufficient reminder of its double‑edged role in proofs.

Here is a proof of the Dominant Form Theorem.

Exemplary Proofs

Using no more than the axioms and theorems recorded so far, it is possible to prove a multitude of much more complex theorems. A couple of all‑time favorites are listed below.

Resources

cc: FB | Logical Graphs • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science