The clock indicates the moment . . . . but what does

eternity indicate?

— Walt Whitman • Leaves of Grass

A One‑Dimensional Universe (concl.)

It might be thought an independent time variable needs to be brought in at this point but it is an insight of fundamental importance to realize the idea of process is logically prior to the notion of time. A time variable is a reference to a clock — a canonical, conventional process accepted or established as a standard of measurement but in essence no different than any other process. That raises questions of how different subsystems in a more global process can be brought into comparison and what it means for one process to serve the function of a local standard for others. Inquiries of that order serve but to wrap up our present puzzles in further riddles and are far too involved to be handled at our current level of approximation. We’ll return to them another time.

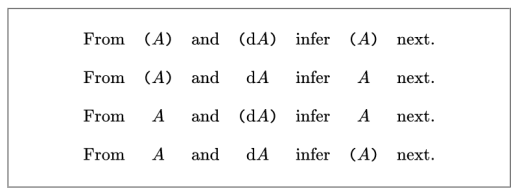

Observe how the secular inference rules, used by themselves, involve a loss of information, since nothing in them tells whether the momenta are changed or unchanged in the next moment. To know that one would have to determine

and so on, pursuing an infinite regress. In order to rest with a finitely determinate system it is necessary to make an infinite assumption, for example, that

for all

greater than some fixed value

Another way to escape the regress is through the provision of a dynamic law, in typical form making higher order differentials dependent on lower degrees and estates.

Resources

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Research Gate