Differential Expansions of Propositions

Panoptic View • Difference Maps

In the previous post we computed what is variously described as the difference map, the difference proposition, or the local proposition of the proposition

at the point

where

and

In the universe of discourse the four propositions

can be taken to indicate the so‑called “cells” or smallest distinguished regions of the universe, otherwise indicated by their coordinates as the “points”

respectively. In that regard the four propositions are called singular propositions because they serve to single out the minimal regions of the universe of discourse.

Thus we can write so long as we know the frame of reference in force.

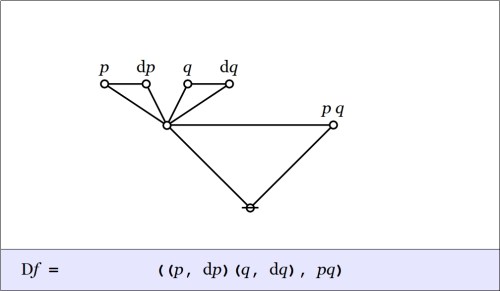

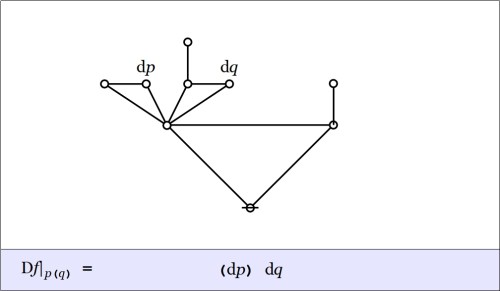

In the example the value of the difference proposition

at each of the four points

may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below.

The easy way to visualize the values of the above graphical expressions is just to notice the following graphical equations.

Adding the arrows to the venn diagram gives us the picture of a differential vector field.

The Figure shows the points of the extended universe indicated by the difference map

namely, the following six points or singular propositions.

The information borne by should be clear enough from a survey of these six points — they tell you what you have to do from each point of

in order to change the value borne by

that is, the move you have to make in order to reach a point where the value of the proposition

is different from what it is where you started.

We have been studying the action of the difference operator on propositions of the form

as illustrated by the example

which is known in logic as the conjunction of

and

The resulting difference map

is a (first order) differential proposition, that is, a proposition of the form

The augmented venn diagram shows how the models or satisfying interpretations of distribute over the extended universe of discourse

Abstracting from that picture, the difference map

can be represented in the form of a digraph or directed graph, one whose points are labeled with the elements of

and whose arrows are labeled with the elements of

as shown in the following Figure.

Any proposition worth its salt can be analyzed from many different points of view, any one of which has the potential to reveal previously unsuspected aspects of the proposition’s meaning. We will encounter more and more such alternative readings as we go.

Resources

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Research Gate

Pingback: Survey of Differential Logic • 7 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Survey of Differential Logic • 7 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Survey of Differential Logic • 8 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Survey of Differential Logic • 8 | Systems Community of Inquiry