Soon after I made my third foray into grad school, this time in Systems Engineering, I was trying to explain sign relations to my advisor and he — being the very model of a modern systems engineer — asked me to give a concrete example of a sign relation, as simple as possible without being trivial. After much cudgeling of the grey matter I came up with a pair of examples which had the added benefit of bearing instructive relationships to each other. Despite their simplicity, the examples to follow have subtleties of their own and their careful treatment serves to illustrate important issues in the general theory of signs.

Imagine a discussion between two people, Ann and Bob, and attend only to the aspects of their interpretive practice involving the use of the following nouns and pronouns.

“Ann”, “Bob”, “I”, “you”.

- The object domain of their discussion is the set of two people

- The sign domain of their discussion is the set of four signs

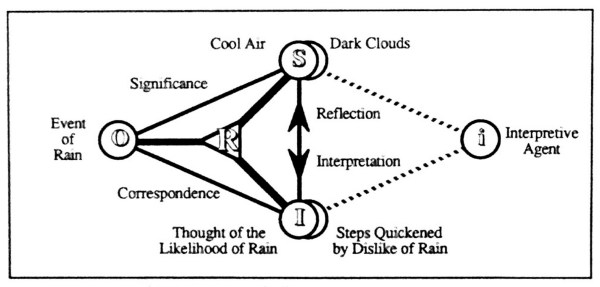

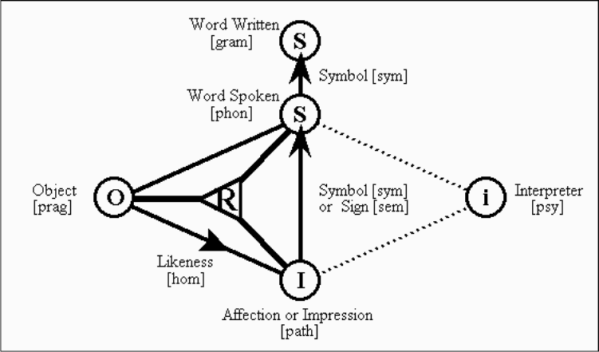

Ann and Bob are not only the passive objects of linguistic references but also the active interpreters of the language they use. The system of interpretation (SOI) associated with each language user can be represented in the form of an individual three-place relation known as the sign relation of that interpreter.

In terms of its set-theoretic extension, a sign relation is a subset of a cartesian product

The three sets

are known as the object domain, the sign domain, and the interpretant domain, respectively, of the sign relation

Broadly speaking, the three domains of a sign relation may be any sets at all but the types of sign relations contemplated in formal settings are usually constrained to having In those cases it becomes convenient to lump signs and interpretants together in a single class called a sign system or syntactic domain. In the forthcoming examples

and

are identical as sets, so the same elements manifest themselves in two different roles of the sign relations in question.

When it becomes necessary to refer to the whole set of objects and signs in the union of the domains for a given sign relation

we will call this set the World of

and write

To facilitate an interest in the formal structures of sign relations and to keep notations as simple as possible as the examples become more complicated, it serves to introduce the following general notations.

Introducing a few abbreviations for use in this Example, we have the following data.

In the present example,

Tables 1a and 1b show the sign relations associated with the interpreters and

respectively. In this arrangement the rows of each Table list the ordered triples of the form

belonging to the corresponding sign relations,

The Tables codify a rudimentary level of interpretive practice for the agents and

and provide a basis for formalizing the initial semantics appropriate to their common syntactic domain. Each row of a Table lists an object and two co-referent signs, together forming an ordered triple

called an elementary sign relation, in other words, one element of the relation’s set-theoretic extension.

Already in this elementary context, there are several meanings which might attach to the project of a formal semiotics, or a formal theory of meaning for signs. In the process of discussing the alternatives, it is useful to introduce a few terms occasionally used in the philosophy of language to point out the needed distinctions. That is the task we’ll turn to next.

Resources

cc: FB | Semeiotics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science