Cactus Language for Propositional Logic

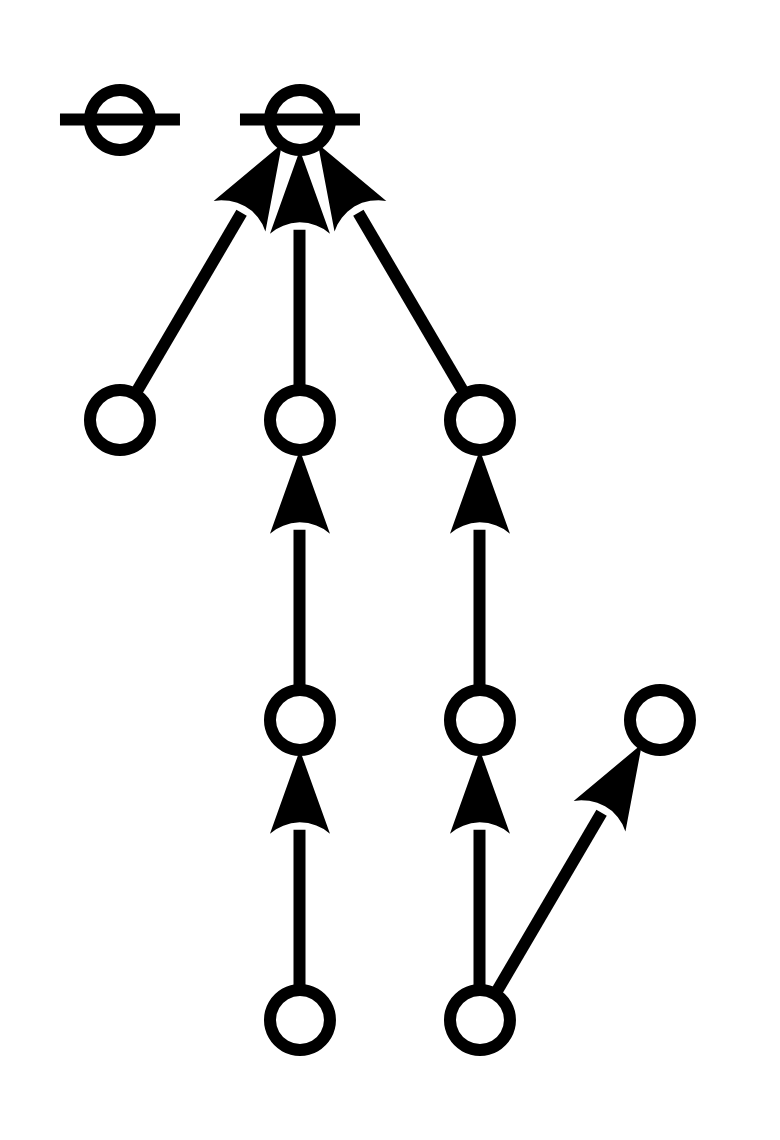

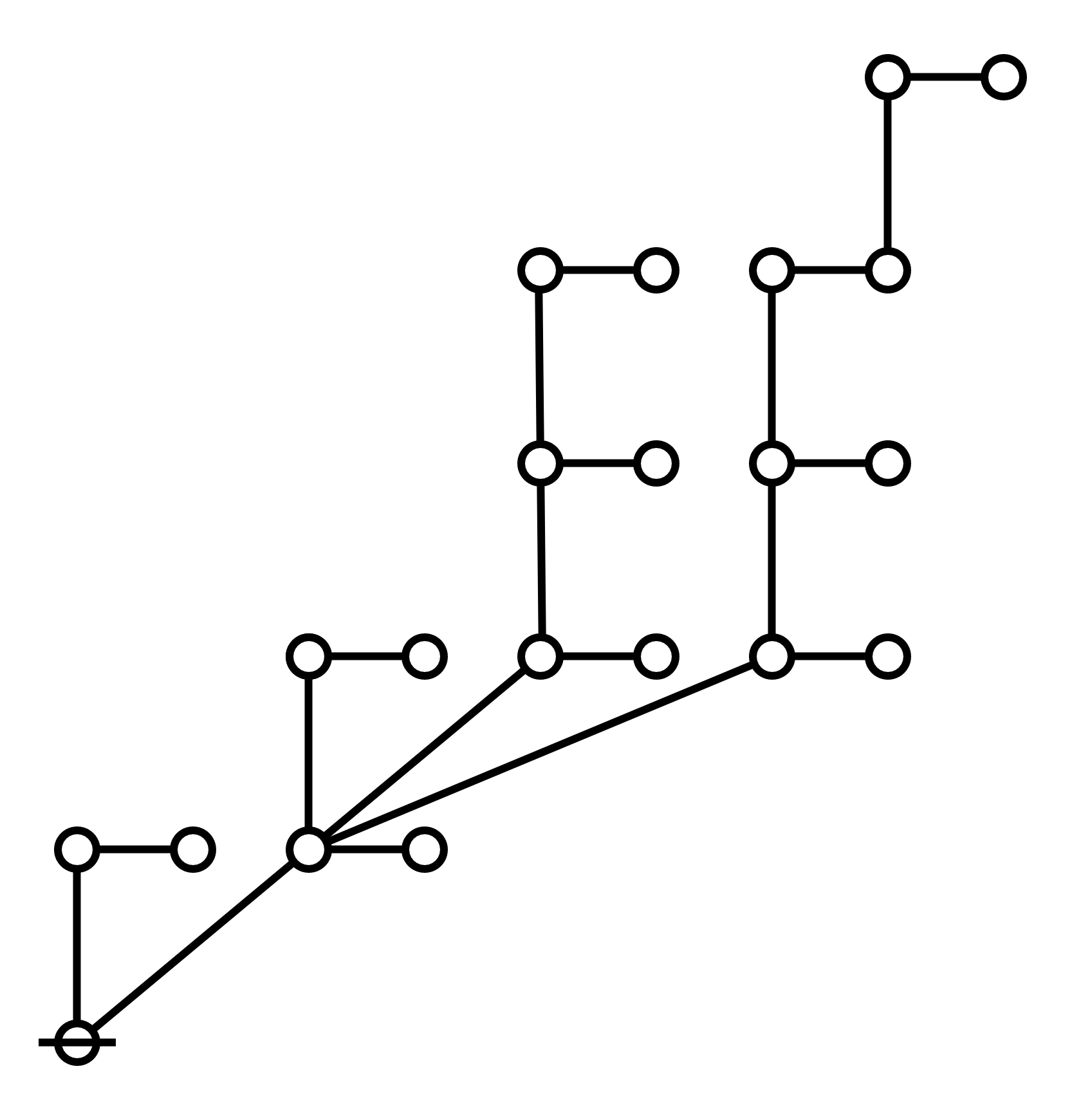

The development of differential logic is facilitated by having a moderately efficient calculus in place at the level of boolean‑valued functions and elementary logical propositions. One very efficient calculus on both conceptual and computational grounds is based on just two types of logical connectives, both of variable -ary scope. The syntactic formulas of that calculus map into a family of graph-theoretic structures called “painted and rooted cacti” which lend visual representation to the functional structures of propositions and smooth the path to efficient computation.

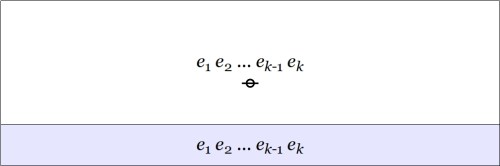

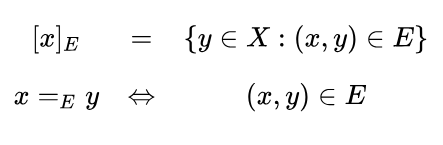

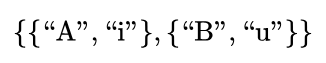

The first kind of connective is a parenthesized sequence of propositional expressions, written to mean exactly one of the propositions

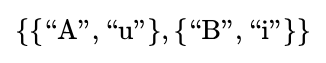

is false, in short, their minimal negation is true. An expression of that form is associated with a cactus structure called a lobe and is “painted” with the colors

as shown below.

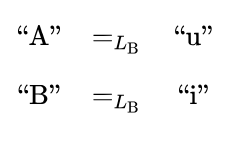

The second kind of connective is a concatenated sequence of propositional expressions, written to mean all the propositions

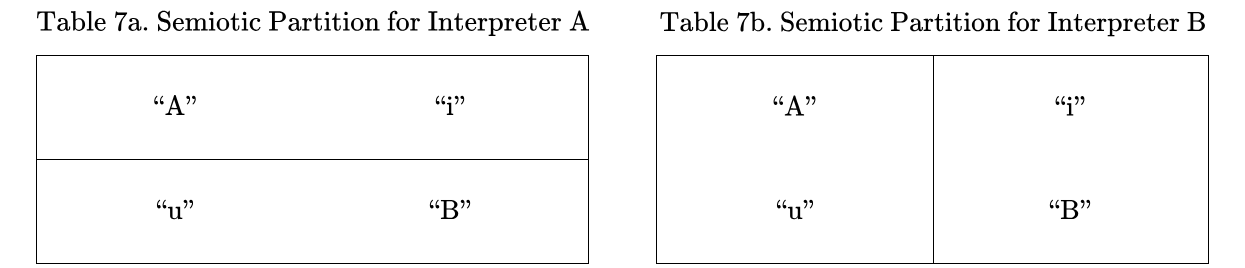

are true, in short, their logical conjunction is true. An expression of that form is associated with a cactus structure called a node and is “painted” with the colors

as shown below.

All other propositional connectives can be obtained through combinations of the above two forms. As it happens, the parenthesized form is sufficient to define the concatenated form, making the latter formally dispensable, but it’s convenient to maintain it as a concise way of expressing more complicated combinations of parenthesized forms. While working with expressions solely in propositional calculus, it’s easiest to use plain parentheses for logical connectives. In contexts where ordinary parentheses are needed for other purposes an alternate typeface may be used for the logical operators.

Resources

- Logic Syllabus

- Minimal Negation Operator

- Survey of Differential Logic

- Survey of Animated Logical Graphs

cc: Academia.edu • Cybernetics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon (1) (2)

cc: Research Gate • Structural Modeling • Systems Science • Syscoi