Interpretation and Inquiry

To illustrate the role of sign relations in inquiry we begin with Dewey’s elegant and simple example of reflective thinking in everyday life.

A man is walking on a warm day. The sky was clear the last time he observed it; but presently he notes, while occupied primarily with other things, that the air is cooler. It occurs to him that it is probably going to rain; looking up, he sees a dark cloud between him and the sun, and he then quickens his steps. What, if anything, in such a situation can be called thought? Neither the act of walking nor the noting of the cold is a thought. Walking is one direction of activity; looking and noting are other modes of activity. The likelihood that it will rain is, however, something suggested. The pedestrian feels the cold; he thinks of clouds and a coming shower.

(John Dewey, How We Think, 6–7)

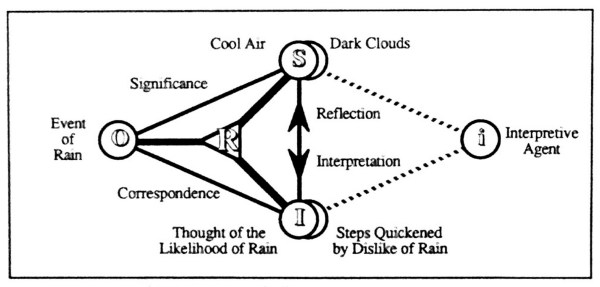

In Dewey’s narrative we can identify the characters of the sign relation as follows. Coolness is a Sign of the Object rain, and the Interpretant is the thought of the rain’s likelihood. In his description of reflective thinking Dewey distinguishes two phases, “a state of perplexity, hesitation, doubt” and “an act of search or investigation” (p. 9), comprehensive stages which are further refined in his later model of inquiry.

Reflection is the action the interpreter takes to establish a fund of connections between the sensory shock of coolness and the objective danger of rain by way of the impression rain is likely. But reflection is more than irresponsible speculation. In reflection the interpreter acts to charge or defuse the thought of rain by seeking other signs the thought implies and evaluating the thought according to the results of that search.

Figure 2 shows the semiotic relationships involved in Dewey’s story, tracing the structure and function of the sign relation as it informs the activity of inquiry, including both the movements of surprise explanation and intentional action. The labels on the outer edges of the sign‑relational triple suggest the significance of signs for eventual occurrences and the correspondence of ideas with external orientations. But there is nothing essential about the dyadic role distinctions they imply, as it is only in special or degenerate cases that such projections preserve enough information to determine the original sign relation.

References

- Awbrey, J.L., and Awbrey, S.M. (1995), “Interpretation as Action : The Risk of Inquiry”, Inquiry : Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines 15(1), 40–52. Archive. Journal. Online (doc) (pdf).

- Dewey, J. (1910), How We Think, D.C. Heath, Boston, MA. Reprinted (1991), Prometheus Books, Buffalo, NY. Online.

cc: FB | Semeiotics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

Pingback: Interpreter and Interpretant • Discussion 1 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Survey of Semiotics, Semiosis, Sign Relations • 5 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Interpreter and Interpretant • Discussion 3 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Interpreter and Interpretant • Discussion 4 | Inquiry Into Inquiry