Questions about the relationship between “interpreters” and “interpretants” in Peircean semiotics have broken out again. To put the matter as pointedly as possible — because I know someone or other is bound to — “In a theory of three‑place relations among objects, signs, and interpretant signs, where indeed is there any place for the interpretive agent?”

By way of getting my feet on the ground with the issue I’ll do what has always helped me before and review a small set of basic texts. Here is the first.

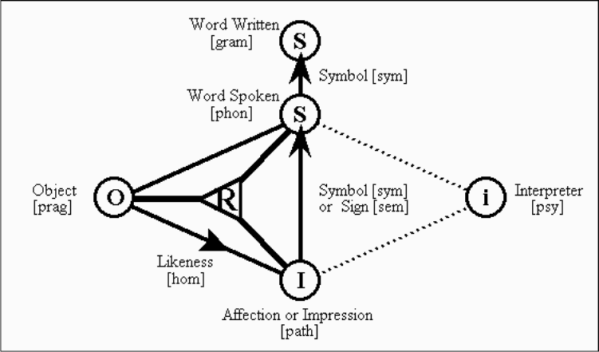

Words spoken are symbols or signs (symbola) of affections or impressions (pathemata) of the soul (psyche); written words are the signs of words spoken. As writing, so also is speech not the same for all races of men. But the mental affections themselves, of which these words are primarily signs (semeia), are the same for the whole of mankind, as are also the objects (pragmata) of which those affections are representations or likenesses, images, copies (homoiomata). (Aristotle, De Interp. i. 16a4).

References

- Aristotle, “On Interpretation” (De Interp.), Harold P. Cooke (trans.), pp. 111–179 in Aristotle, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London, UK, 1938.

- Awbrey, J.L., and Awbrey, S.M. (1995), “Interpretation as Action : The Risk of Inquiry”, Inquiry : Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines 15(1), 40–52. Archive. Journal. Online (doc) (pdf).

cc: FB | Semeiotics • Laws of Form • Mathstodon • Academia.edu

cc: Conceptual Graphs • Cybernetics • Structural Modeling • Systems Science

Pingback: Interpreter and Interpretant • Discussion 1 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Interpreter and Interpretant • Discussion 2 | Inquiry Into Inquiry

Pingback: Survey of Semiotics, Semiosis, Sign Relations • 5 | Inquiry Into Inquiry